Dr Angela Puca AP: Hello everyone I’m Dr Angela Puca and welcome to the Livestream symposium, and today we have a very special guest. First of all thank you all, for everybody in the chat. I can see that some of you guys are here and thank you Andrew and Edward for moderating the chat.

Today we are going to talk about something that is very difficult to find in English, I would say, and that is the Roman Reconstructivist Movement, and we have a special guest Marco Castagnetto a PhD candidate at the University of Turin and fellow Metalhead, as we were discussing just before the live in private. So thank you so much for gifting us your knowledge because this is also the topic of your PhD, isn’t it Marco?

Marco Castagnetto MC: Thank you very much, Angela. Very nice to be here and most of all it’s very nice to find some kind of interest in this topic because it’s a very kind of neglected knowledge in the academy. And so I think that this is really a nice chance to share some ideas about Roman Traditionalism, as you call it, and so thank you, thank you very much.

AP: Thank you for being here. Another thing that I was thinking about is that now my audience will think that all Italian scholars are named Marco because I’ve had a few Marcos…

MC: Yeah, probably, probably it is.

AP: How are you today, Marco?

MC: I’m very fine and I think that today is a very cloudy day here in Turin.

AP: Well, I live in England so…

MC: Okay, okay. They’re quite used to this kind of climate and no surprise for me to find that kind of climate.

AP: So but coming from Naples, Naples is very different.

MC: Yeah, I know, I know. I’ve been many times there. It’s a city I love, I really love and I’ve been there also because it’s a city that has very interesting things about traditionalism and the history of Italian Esotericism in the 20th century, yeah.

AP: Yeah, so let’s crack on and before we do actually I’d like to remind everybody in the chat that if you have a question just SuperChat it so that I can put it on screen and Marco can answer it. So Marco, let’s talk about the Roman Reconstructivist Movement then. Let’s start with the history. When does it start and you know, what are the key moments?

MC: Yeah, in a very preliminary way, we could define Roman Reconstructionism more properly, I think, as Roman Traditionalism, and I would like to better specify this distinction. As we all know, there is a wide debate in the academy about the distinction between emic and etic perspectives and how these approaches can influence and even shape studies of religious or magical movements. Here, the Roman case is exactly a paradigmatic example of how the definition commonly used by scholars, that is, of the so-called Pagan Studies, the definition used to define this particular field and namely that of Roman Reconstructionism is particularly, is very unpleasant to practitioners themselves. Why? Certainly, the Roman case is not the only one because many phenomena of contemporary paganism reject the definition for different reasons. But the modern revival of the ancient Roman religion has some specific features that show how the broad framework of Pagan Studies is a label, a kind of label to which we can recognise an introductory validity but within which there are irreconcilable and sometimes even antithetical differences.

So, let’s go a little deeper into the problem of definition, which I think is a kind of pivotal problem. A definition that could probably better meet the favour of the practitioner is that of the Roman Way to the Gods, which is more or less the way they call their own beliefs and practices. The word ‘way’ has a complex semantic value containing at least three complementary perspectives. So first of all it is a modus, which is to say a lifestyle, so that it preserves, in some way, a fundamental feature of the way traditional societies related to the sacred. That does not provide for a distinction between the different spheres – to put it better, the social, political, economic and religious life of traditional society is not divided into autonomous or separate spheres. Still, it’s a holistic whole, so they act on each other and then distribute the effects on all levels, on all planes, as when relating to a conception of life that provides for a pact between men and gods. They see this pact as a guarantee of preserving the cosmic order and preserving the life of civilization, of Roman civilization itself.

So thus, the second aspect is that the definition of the Roman Way to the Gods is a relational feature and also a sense of movement that highlights, in some way, the chance and the type of relationship. So, the chance is to set up a journey toward the gods while the relationship is that of a more intimate reciprocity. This way of understanding religious life takes on a deeper meaning in a nation such as Italy, where Christian ontology, the whole Christian ontology, has exercised a kind of monopoly for an incredibly long period.

And finally, the term Roman Way implies the chance of other, that are potentially infinite ways. And this, I think, it’s a kind of homage to the mentality, to the thinking of pagan authors who responded to the Christian polemicist literature in which they saw an incompressible exclusivist that legitimises only one way of relating to the sacred that is precisely that of the new Christian religion. I think it should also be noted that practitioners of the Roman Way to the Gods understand tradition in what I call an eminent sense which is to say tradition with a capital T. Yeah, to distinguish from a different way to intend tradition; that is the transmission of customs from one generation to another, from father to the son. It’s quite interesting to point out that this vision of tradition can be the motivation, also – can motivate the interests of many traditionalists in Hindu-European Studies. The concept, for example, the concept of Sanātana Dharma with which the Hindu tradition refers to the doctrinal basis, of what we normally call Hinduism, is very much seen in the sense that Roman traditionalist circles are used to portray their beliefs. That is a sort of perennial norm that is perennial precisely because it has a kind of scientific value representing, in their way of understanding the world, the very structure that is both spiritual and material of the entire cycle of manifestation of the world.

I must admit that there are currents in Roman traditionalism that instead recognise the reconstructionist nature of their beliefs. But I mean this is not the only perspective and in some way, it’s not the most important, the most shared, between practitioners. I would like to make a distinction here if I can.

AP: Yes, absolutely.

MC: We can divide Roman traditionalism into three doctrinal areas and three periodisations. I would like to introduce them, starting with the historical taxonomy briefly. I distinguish Roman traditionalism between an embryonic period, a classical period, and a contemporary one.

CC BY-SA currybet

The first period is probably the second half of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th. In this first, in this early period, traditionalist content emerged on the Italian cultural and public scene. This was due to the work of some intellectuals, artists, and even scholars who were supposed to have contacts with traditionalist circles that remained in secrecy until then. And we can identify some crucial moments of this first period, the first era. First, the figure of the archaeologist Giacomo Boni was born in 1859 and died in 1925. That was the man, a very nice guy who discovered the Lapis Niger, that the tradition wants to be the burial place of Romulus himself. This particular stone has an inscription with one of the oldest written evidence of the Latin language that is dateable – around 575-550 before Christ. Boni’s archaeological research was highly influenced by his relationship with the esoteric environment of its time. And for example, he attended the home of Emmelina De Renzis; she was the mother of Giovanni Antonio Colonna di Cesarò, who was a prominent anthroposophist and was in correspondence with Leone Caetani, who was another key figure in Italian esotericism of that time. Then a second very important fact for this first period is the writing of a play, a drama by Roggero Musmeci Ferrari Bravo that was known as ignis…

AP: A long name.

AP: Yeah because nobody wanted to say his long name.

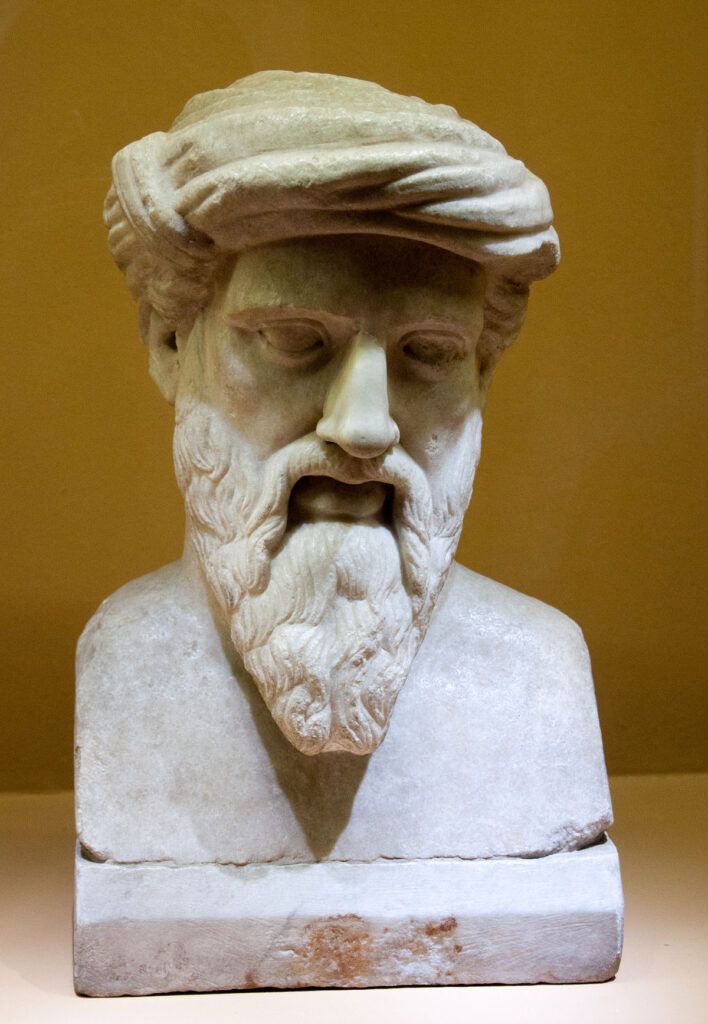

MC: Nobody wanted to see it, and while it could read it on the tablet, maybe ignis is relatively better, and this drama was entitled Rumon: Sacrae Romae Origines. And Musmecimet, another key figure, was Evelino Leonardi, an exponent of the so-called scola italica. It was a sodalitium, a Neopythagorean sodalitium, and he did some studies on the Divine Proportion and took a deeper interest in Pythagorean issues. And finally, there is, of course, the work of intellectuals such as Angelo Mazzoldi or Chiron Espilandi or Nietzsa Champi, in particular, the work of Angelo Mazzoldi wrote the Origine Italiche so it is about Italic origins. That’s a work in which he argued that the prevailing opinion among scholars, considering Greece and Egypt as the very cradles of Western civilization, was in some way wrong. This primacy had to be ascribed, in the words of Mazzoldi, to the ancient peoples who inhabited the Italian Peninsula. And Mazzoldi went so far with his theories as to have identified none other than Atlantis in ancient Italy, as Plato mentioned.

AP: Was this in a specific place in Italy, or…?

MC: Particularly because it was portraying a particular map of Italy that was bigger than the usual peninsula that we’re used to.

AP: Okay.

MC: It was larger than water, and the sea submerged a part of it, leaving the figure of Italy we all know. That is how the sea submerged Atlantis, and the myth was about submerging a part of Italy.

Also, I could say the classic period of Roman traditionalism is the second period. With the years that passed from the emergence of a quite important reality, there was the group of UR. The period led up to 1974, the year of the death of the philosopher Julius Evola, who was the first writer of the magazines UR and then KRUR with two magazines tied to the group of UR. By the way, UR stands for fire or a bull in Chaldean or is a German root for something like original, primaeval and prototypical. So the group of UR was a composite esoteric association because it welcomed a lot of personalities with very different backgrounds, Julius Evola or Arturo Reghini, who was a Freemason and a follower of Neopythagoreanism of Rocco Armentano and the anthroposophist Giovanni Colazza, and this was just to name a few of them.

AP: What was the group of UR or the UR group?

MC: The UR group was a magical sodalitium because the aim was to build a magical chain with two main targets. The first was to influence Italy’s political scenario, and the second was to contribute with a magical chain to the spiritual uprising and spiritual development of every single member of the sodalitium. The group was in some way kind of a meteor and was meeting a couple of years ago, but I think its legacy in Roman traditionalism. Still, in the wider esoteric scenario of Italy, it was of enormous, very huge importance. I want to emphasize that the two magazines published in the group UR were titled UR and then KRUR, which had very eclectic content reflecting the group’s composition. There are pieces by Plotinus and Iamblicus; they also published the Golden Verses of Pythagoras, some alchemical texts som,e passages of the Majjhima Nikāya, a part of the first chapter of Guhyagarbha Tantra and much much more. This was probably one of the most important experiences in the Roman tradition of this…

AP: What were they doing in the group of UR?

MC: You know, I think that the eclectic frame of the publications somehow reflects the kind of practices that we were working on. To give some examples, Evola was involved in a kind of practice that he assumed from both Tantric sources but adapted to a kind of Roman general framework. There is a practice that is not described in UR or KRUR; there is a kind of meditation with the practitioner having to act as if he was the god he’s talking about and is evocating in some way. But, for example, Giovanni Colazza has another kind of practice as he was one of the main disciples of Rudolph Steiner in Italy. So his practices were the ones that anthroposophy is quite famous for inner exercises and meditational practices. And these were the very wide spectrum of practices inside the group of UR. But what united them all was, as I told you before, a will to influence Italy’s political scenario and work together so that the chain work could improve their aesthetics. Yeah, these, I think, are the main aims of the group of UR.

AP: And what about Julius Evola? Many people are interested in or despise him, so he is a polarizing figure but influential. Could you tell us more about him?

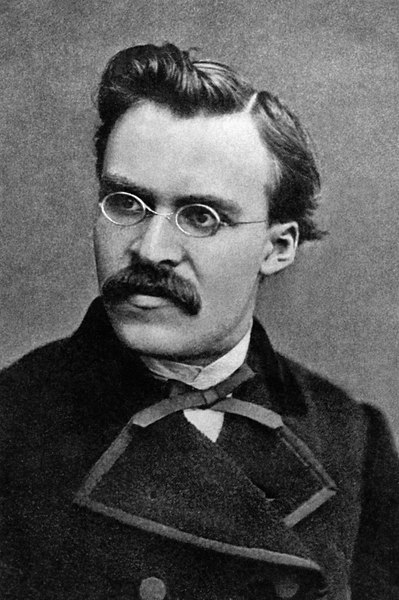

MC: Yeah, I think he was considered a philosopher, clearly in terms of a conservative revolution philosopher and an esotericist. Still, he is quite more famous for his political ideas and for the influence he had on the Italian extreme right after fascism. I think it’s quite easy to dismiss Julius Evola as a kind of bad master, an evil master or the Black Baron, as he was called here in Italy. But it’s quite a way because it was a more complex figure. I think that Evola attempted to resolve what he perceived as the very contradiction of idealism, and they tried to do so to reach this target by the construction of the notion of the absolute individual.

AP: Very Nietzsche.

MC: Yeah, yeah, very Nietzschean. I also think this was somehow his interpretation of the Hindu concept of Atman as a principle responsible for the whole manifestation. We must remember that Evola started being a Dadaist initially; he was a painter and artist in the Dada movement. And the second thing is that his thoughts were highly criticized by fascist intellectuals and from the Reich from the German Reich. For example, Ugo Spirito was a prominent fascist scholar and intellectual. He considered his doctrinal attempts to be very derivative and, in some way, megalomaniac.

On the other hand, many National Socialist Party officials suspected him of being against their pan-Germanic view. Of course, they were right, as Evola’s idea was one of Italian Supremacy. I think that what resulted was what the scholar Stephen Meyer described as a kind of magic idealism. Stephen Meyer described it in this way: part Tantric, part primitive Buddhism, part Pagan, and part medieval Alchemy. I think it’s quite a nice way to describe Julius Evola’s ideas. Some steps in his life are fascinating and crucial.

AP: Excuse me a second though, we have a question, do you know if Collin Wilson was influenced by Evola in regard to the issue of fascism?

MC: Yeah, I think, because Evola was in some way a figure, how to say, here in Italy there are many associations, many groups that refer to the teachings, to the doctrine of Julius Evola. But I think he has been more and more influential outside Italy because it’s quite difficult in Italy to research Julius Evola and his ideas seriously. There’s a kind of social stigma against his ideas, and I think this is a problem because studying a phenomenon doesn’t mean we have to adhere to that kind of thought, of course.

AP: Yeah, I’m totally with you on that. I think we need scholarships for everything because everything is essential, even things we do not agree with. You know, you don’t just exclude things that you don’t agree with from study and research; that’s not how knowledge works.

MC: Yeah, and also, I think that, as a scholar, I don’t want to have the problem of justifying my studies, declaring in some way that I would not participate in those ideas for a methodological reason.- I’m supposed to be uninvolved in that idea I’ve been standing on because I have a methodological detachment from the object I study. I’m a scholar, and I must separate my personal positions. That could be political, religious or even generally social from my area of research. The thing is that in Italy, it’s still very difficult to research Julius Evola, and this is quite different, for example, in the UK or the United States. I don’t mean that there is no prejudice against Julius Evola because it’s present, of course, but Julius Evola has highly influenced many different thinkers who had a career. This is not an example of a scholar, but you can think of another controversial figure, Alexander Dugin. Julia Evola’sEvola’s thoughts very much influenced him. And I think there are a bunch of books by Evola that are in some way crucial to understanding his influence both on the political frame and the religious one. The first is “Pagan Imperialism” – an adaptation of a pamphlet with the same title by Arturo Reghini that Evola developed and published in 1928.

It was one of the prominent extreme right parties, an extreme right organisation because it was before a cultural and political organisation. Guidelines Julius Evola’s Guidelines were set up as an agenda of action by Ordine Nuovo, but it was active from 1956 to 1969. One year after the publication of “Guidelines”, Julius Evola was arrested for being the theorist of an extreme right organisation called the Fascio d’Azione Rivoluzionaria, FAR. There was a peculiar defence of Julius Evola because he said and wrote that it was not his fault if some guys decided to act in that way because he never wrote anything that was in some way, that’s in some way to be considered an inspiration for violent action. So the debate was, was Julius Evola a bad master or was Ordine Nuovo formed from very bad disciples? This is the main topic of his influence on the extreme right.the extreme right.

AP: And what about the influence? Do you think Julius Evola’s right-wing thoughts also influenced the Roman Reconstructivist Movement we have today?

MC: You’re asking about a contemporary phase of Roman traditionalism? I can say that Julius Evola is in some way more influential now than he was before. But contemporary Roman traditionalism is more articulated. We have very small groups, very small organisations and a very big part of them still considers Julius Evola as a big influence. But there are also smaller groups that are trying to detach from this kind of past. Particularly, I’ve been talking with a lot of people from these groups that consider all the first and the second period, to use my distinction, as very problematic to legitimate Roman Traditionalism in the public sphere. And so they are trying to develop different forms of traditionalism, just interpreting the sources, the ancient sources and leaving all this controversial past in the dust, yeah.

MC: Yeah, yeah, I’m mainly talking about groups in Rome. Yeah, the problem of the relation between traditionalism and politics is that the Roman traditionalists tried a sacralisation of politics. That implies a politicisation of the sacred, necessarily. Necessarily, the relationship between politics and traditionalism is, in fact, a constitutive feature of the whole phenomenon, at least in regards to the very early period in the classical one as one of the first historical events that are for Roman traditionalism, as a protagonist, was a movement that advocated the intervention of Italy in the First World War. This war was interpreted as a great Roman war that aimed to bring Italy back to what was perceived as its natural borders, defined by Emperor Augustus. All the traditionalists of the first period were deeply convinced of the Italian intervention and in this context in a particular context after the First World War and then of the idea that the movement developed through the developing fascism.

There is an episode, and still, many perplexities are hanging for a few scholars interested in this issue. And that was – we were going to the Second World War. Someone decided to offer Benito Mussolini fasces composed of a bronze axe that is thought to come from an Etruscan tomb. This very ancient Etruscan tomb is similar to some preserved in the Etruscan Museum. This axe was surrounded by 12 birch rods tied with red leather strips. And this was, according to some traditional prescriptions. Since Mussolini was seen as a possible protector of the Romanisation of Italy, some rites were celebrated to propitiate a more Roman Italian state. For example, a celebration to propitiate the March of Rome in 1922 was celebrated, for example, the ‘Cerebis Mundus, Ludus Troiae, Ludi Palatini – a lot of rights were celebrated to propitiate this kind of more Rome-inspired politics by Mussolini. But I think this relation is one of traditionalism and politics as a black box; you know, as a scholar and individual, I’m very interested in the concept of the black box as Bruno Latour described it. I think a lot of, mainly all social aggregates, such organisations are a kind of black box.

AP: What do you mean?

MC: It is a kind of a box of secrets. We know a lot and have a lot of information about Italian esotericism in the 20th century. But there’s also a black box that gives us different information about that, and you know, I think that a black box is constructed, it contains three kinds of different information. Some of them are original and so reliable, some of them could be reliable, and some of them are false. Much scholarship about Italian esotericism and Roman traditionalism is based on these three documents. Let me try an example if we can go a little deeper into the black box. We all know the Red Brigades of Italy, Il Brigate Rosse was one of the leading far-left militant associations that were responsible for violent incidents inc, including the abduction and murder of the former Prime Minister Aldo Moro during the so-called Anni di piombo Years of Lead in Italy. They were, in effect, a kind of terroristic association.

Well, some BR activities were planned and discussed in a centre in Paris called Hyperion, which was supposed to be a language school founded in 1877. But the centre was then suspected of having relations with various far-left terrorist groups but also with the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States and even Mossad. So even the right party had its hidden centre beyond the Alps and specifically, in Lugano, there was a villa on the lake near Lugano with a very nice conference room and a beautiful fountain square in it, and this was named Villa Favorita and was the one of Baron von Thyssen and a man like Delfo Zorzi frequently visited this very rich house. Delfo Zorzi was one of the men in the Gladio, the Italian branch of the Western Union stay-behind organization and then one directed by NATO and the Central Intelligence Agency. Villa Favorita was also frequently visited by very central names of Roman Traditionalism. In those particular circumstances, we can see particular relations between that kind of frame, the traditionalist frame of that period and the political one.

AP: How so?

MC: Because at Villa Favorita intertwined some plots of the subversive right, but also there were magical environments in groups that would have been then close to very famous political parties in Italy because the political scenario in Italy was rapidly changing, was changing very fast. After the dismissal of the Movimento Sociale Italiano, the main far-right party after fascism, different strategies were needed to gain some influence on the whole political frame in Italy, and that’s the reason why. Also, the attitude of some traditionalists, but I have to say that more than traditionalists meeting in Villa Favorita, we have to say that there were people interested in Esotericism, in a wider sense of Italian Esotericism. The relationship between Esotericism and politics in Italy is very strong; it’s always been strong, and traditionalism is one of the shapes it took during its development.

AP: So, do you mean that even today, Esotericism in Italy is linked strongly with politics?

MC: Oh yeah, yeah.

AP: Do you mean with right-wing politics or generally with politics?

MC: Yeah, in some ways nowadays, how can I say the difference? The old dialectic between right and left in the esoteric field is more nuanced. But yeah, it’s a relationship that is still alive, and I don’t think that is – how can I say that in the past, in the early periods was in some original fascism, it was stronger, it was more explicit.

AP: I think that I would say that for instance a lot of Pagans, contemporary Pagans, I know that sometimes they are referred to as Neopagans, they tend to be much more left-leaning.

MC: Yeah of course, of course, yeah.

AP: So and I was thinking about them.

MC: Yeah, a small but interesting book was published in the frame of Roman Traditionalism some years ago. That is about the problem of contemporary Paganism, and in that book, that kind of Paganism, that is one that we can describe as including Heathenry, Wiccan, Neoceltic, Druidism and so on, are considered to be a kind of aberration, due to two main reasons. One is that Roman Traditionalism is conceived the personal; they do not consider the personal choice of religion because they say that spirituality is not a matter of individual choice but is tied to history, that is, the ancestors and to the place where you live. Italy is called by Roman Traditionalists Saturnia Tellus, where Saturn, the God Saturn, lived and is still underground. This presence, this divine presence, permeates the entire land and, through it, all its inhabitants. So, the fact that many people are into contemporary Paganisms, which are different from Roman Traditionalism, of course, has decided that faith and spiritual participation are considered a kind of modern approach. In this point, we can see a very interesting echo of Julius Evola’s thought because Roman Traditionalism strongly emphasises the critique of the modern world. The critique of its values, its way of life, its political ideas, and its economic directions.

AP: So, is it easier to search for a golden age in the past?

MC: I think they have, in some way, the deep conviction that this has to happen. We are going, which is another echo of Hindu thought because we are at the end of the Kali Yoga or the Iron Age. The same is true with a more traditionalist Roman lexicon, which will necessarily lead to a new Golden Age. And what they, or at least a big part of them and mainly from the very first, the early organisation in groups, have been working for is to keep that kind of flame alive.

AP: So, but if you were to narrow down the main traits of Roman Traditionalism, what would they be? So the first one would be like the refusal of modernity and aspects of modernity. Because they want to go back to this ideal, right? What would be the others?

As I mentioned before, I make a further distinction in three doctrinal areas, which is what makes Renato Del Ponte, that is the founder of the MTR, the movimento tradizionalista romano, the Roman Traditionalist Movement and one of the main groups of the contemporary era. The first group, the first area which we may define as conservative, accepts the goal of revering the Roman religion that flourished between the origins of Rome and the Punic wars. They are inspired by the so-called Scriptores Rerum Prussicarum, the authors of old things, for example, Varro, Virgil or Cato the Elder. The second area focuses on the precision with which rituals were performed, taken from ancient sources – to make another parallel with the Indian world. We can say that this second area is what in Vedanta is Pūrva Mīmāṃsā, with their attention to the details, to every detail of the ritual.

Finally, the third component was very interested in mysteriosophical and metaphysical contents that are more or less absent from the first and second areas. So, incorporating elements of Neoplatonism of Plotinus, Proclus and Iamblicus, among others in this area, I think all three components are deeply convinced of the return of a Golden Age. But they have different ways to help this happen. Anything that is in the third component, the one more interested in mysteriosophical aspects of the ancient religions, we can find a lot of different, a lot of influences coming from different esoteric fields that develop in time, so we can find practices coming from the work of Kremmerz that are the had a very big influence on the Roman traditionalist media.

AP: What was the influence of Giuliano Kremmerz on the historic milieu?

MC: I think that Kremmerz, mainly through the idea of the Osirian Egyptian order. Do you think it’s necessary to introduce the figure of Kremmerz?

AP: Just briefly so that we can…

MC: Yeah, he was born in Naples, and he started his esoteric corpus after he met the Freemason Giustiniano Lebano and Leone Caetani – we’ve been briefly talking about him before. He edited esoteric journals like The Secret World, el mondo segreto Di,agnetic Medicine and the later Commentarium. Then, he established an occult order known as The Fraternity Of Myriam. Many scholars, okay, even though many refer to this feed, are in some way very optimistic, think of a link between Myriam and the so-called Ordine Osiriano Egiziano, which is the Osirian Egyptian Order that was in quite mysterious esoteric order at that time. But this idea is a big misunderstanding because that specific order, which we refer to as Ordine Osiriano Egiziano, has never really emerged in the public sphere. As it simply was not interested in any form of proselytising, but despite this confidentiality, I had the chance to read their history ordinance, that is, the history of the order, and I wasn’t really able to find any reference to members of the Miriamic academias, neither anyone linked In some ways to Kremmerz. Of course, Kremmerz wasn’t on that list. But it’s through this particular esoteric field that the words of Kremmerz did… in the particular magical path of Kremmerz influenced other traditionalists that were… we had to think of Italian Esotericism of that time was not structured in different boxes. But it was a kind of… there’s a flux in it. It was a kind of ocean of different ideas, everyone influencing the others.

AP: Yeah, that’s very interesting, thank you. We have a question, how do Roman Reconstructivists express their religion in the modern day? So what does Roman reconstruction – Reconstructivists look like today?

MC: Yeah, thank you for this question because it’s very interesting. I think there are two ways they express themselves. We have a conservative wing that is in some way getting older, but some new members are joining that kind of conservative traditionalism. Then, we have different groups trying to develop, as we said before, a different way to intend traditionally. There are many social network pages about Roman traditionalism – you can imagine the reaction to that kind of phenomenon in the conservative sector of traditionalism. Many practice rituals as they can read in the ancient sources – where there are no notes on particular parts of the rituals, many simply create them.

AP: I think Ovid is quite popular.

MC: Yeah, but many, the older members and some younger members that in some way have the idea of staying true to the principles are still practising those particular rituals and celebrations that developed during the Evola period. So they’re very particular, very particular. There is a nice story about a Roman practice that had to be transmitted to one of the main groups, the one that proceeded the MTR, that was the group of Dioscuri, and there are legends running in the field about this particular practice that they say was sent to the group, to the Dioscuri group by a bishop, saying that the practice was in the Vatican Library. I know that this ritual is still used and still practised.

AP: It is interesting thank you for the SuperSticker. And can we hear an example ritual? I know a group in Rome that has a YouTube channel and they have some of those rituals, they post some of those rituals and the name of the group is Communitas Populi Romani, I’m gonna write in the chat.

MC: And that’s a leftish group of the…

AP: Yes. Let me write in the chat. Do you know other examples, Marco, of rituals that contemporary reconstructionists would do?

MC: It’s quite easy to find the rituals of a group called Pietas. And I mean, I think that the ritual – if you have contact with them, of course, you have to have contact with them- is very hard in some ways, public. Yeah, but there are many, many of these rituals that are still private because the idea is that the public cult is no longer possible, of course, because there is no political institution that, in some way, will legitimate what the public cult in Ancient Rome was. So just the private cult, and this is, in the ideas of conservative traditionalists, just and simply the private cult could be performed. So they practice in their houses and just in their strict groups.

AP: What kind of reconstructionism do you think is more popular or widespread in Italy nowadays?

MC: Oh, I think that, in quantitative terms, I think that the most, the proper reconstructivist forms of practice are the most widespread. But talking about the intensity of social ties and cultural links, the conservative forms of practising are probably stronger in how they shape mutual relations and group dynamics.

AP: I see. Thank you, Marco I think that we can wrap up our conversation now because I’ve held you, hostage, for over an hour.

MC: I was very happy with that.

AP: Is there anything else that you want to add or do you feel that people should know about Roman Traditionalism or the Roman Reconstructivist Movement so that they can have a better understanding of it?

MC: Oh, no. I think that even if it’s not so easy to find interesting academic books or papers about Roman Traditionalism, I would like to suggest that when researching Italian esotericism but it’s not, of course, not only about Italian Esotericism and Traditionalism, we have to pay a lot of attention to the black box there is a lot more in the black box and it’s quite interesting to find.

AP: Is it like Schrödinger’s cat? Every time that you say black box I think about Schrödinger’s cat and I think is this creature dead or alive?

MC: Dead or alive, yeah, of course.

AP: Or maybe both.

MC: Yeah, yeah.

AP: So yeah, thank you, Thank you so much and oh, thank you very much, Hank has just joined, thank you, Hank. And if you guys have further questions please leave them in the comments and Marco and I will look at the comments and reply whenever we can. But thank you again, Marco, it was lovely having you here and I hope you enjoyed having this conversation.

MC: Thank you very much, I enjoyed it a lot and I really hope we could cross our roads again.

AP: Yes and definitely we need to meet in person, as well.

MC: Yeah, yeah.

AP: So and oh, last thing if people want to find you is there are you on social media at all? Is there a way people can find you?

MC: This is a very paradoxical feature of my life because I am a sociologist and maybe, for this reason, I have no social at all but I have of course email. Is it possible to send it in the chat?

AP: Yes, if you are on YouTube, otherwise I can put it in the info box if you want.

MC: okay, it’s (email address) I’m sure you will be able to write it and so to let people who want to get in touch.

AP: Yes, I will put it in the info box and thank you Father RC for the Super Chat. So thank you again Marco and thank you, everybody…

MC: Thank you very much.

AP: And thank you, to everybody who has attended this conversation and to those who will watch it afterwards. And if you enjoyed this conversation, please don’t forget to SMASH the Like Button, subscribe to the channel, and activate the Notification Bell so you will never miss a new upload from me, if you can help it all, and you want to support this project because this is a crowd-funded project, I would really appreciate it if you consider supporting my work by joining my Patreon, with one-off PayPal donations or by joining Memberships that you find next to the Subscribe Button and otherwise thank you all for the SuperChats and for being here and for being amazing and stay tuned for all the Academic Fun.

Bye for now.

Marco’s contact at Academia.edu