Dr Angela Puca AP: Hello everyone and welcome to the livestream Symposium. As you know I have my PhD and I and a Religious Studies scholar, and this is your online resource for the academic study of Magick. Esotericism, Paganism, Shamanism, and all things occult.

Before I move on to introducing our special guest today I’d like to remind you that Angela Symposium is a crowdfunded project. So if you have the means and want to help this project keep going please consider supporting my work with a one-off PayPal donation, by joining memberships or my Inner Symposium on Patreon. You will find all the links in the info box and in a pinned comment. And of course, don’t forget to smash the like button, subscribe and activate the notification bell and leave us a comment if you’re watching this after we go live. Or you know, let us know what you’re thinking in the chat if you’re here with us live. So let me introduce our special guest now Dr Francis Young.

Hi, how are you today, how do you feel?

Dr Francis Young FY: I’m very well today Angela and it’s great to be speaking to you.

AP: Thank you for being here. You know I’m familiar with your work, I think it’s very interesting and that’s why I wanted to have you on the channel. As I was also mentioning to you before we went live, I also feel like different fields, different disciplines that study Magic or Esotericism or Witchcraft, even from different angles, should probably be communicating more because sometimes I feel like they are a bit too isolated in Academia. So I noticed that even reading your book I got that kind of feeling like we really should have more historians, you know, have more communication with historians because I’m in the field of Religious Studies and Anthropology of Religion and so people may not know but they are different disciplines and sometimes a bit too isolated than they should be.

FY: Yeah, I think that’s very true and I think that I as a historian am very grateful for the perspective of people working in other fields like Religious Studies, Sociology of Religion, Psychology of Religion, and Anthropology. You know I read this stuff and it’s fascinating to me even if I don’t use those methods of inquiry, it’s all really crucial that we’ve got this broad-based understanding of something which is as difficult to grapple with as Magic. It’s not a straightforward historical subject.

AP: Definitely, yeah. And what makes you interested in Magic because I’ve seen that you have worked on it throughout your books. So not just the one that we’re probably going to discuss a bit more in today’s interview which is “Magic in Merlin’s Realm” but yeah, what makes you interested in Magic in your inquiry?

FY: Well I started out as a bit more of a conventional Historian of Religion, you might even say a Church Historian. I was looking at a particular aspect of the History of Christianity. But I became more and more fascinated by deviant beliefs, you know, beliefs that were deemed unacceptable, particularly I suppose, the thing that unites many of my interests is that I’m interested in beliefs that other people think are absurd or other people think are outdated or people shouldn’t be believing that. That it’s, you know, unacceptable for them to go down that road and I’m interested in folklore, I’m interested in old beliefs that linger, in newer societies and things that are resistant to social and cultural change. And so, I suppose, these days I describe myself as a Historian of Religion and Belief. I still work on some of the more conventional stuff. I’m interested in the Cult of Saints, Monastic History, and things like that. But I’m also very interested in the history of supernatural beliefs and particularly Magic and belief in Fairies are things that fascinate me. So yeah “Magic in Merlin’s Realm” came out in 2022. My most recent book “Twilight of the Godlings” is a history of the origins of British Fairy belief and that came out just a couple of weeks ago, actually. So yeah, there’s plenty of work going on.

AP: Yeah, I should probably invite you over again to talk about that book because I’m sure that lots of people in my audience will be interested in that. But why did you focus on Merlin in that book, since you are talking about, you know, the intertwined and intermingling of the occult Magic and history, how come did you choose the… You explained that in the book but I wanted to elaborate more on that, for those who haven’t read, yet, the book, so why did you put Merlin in the title?

FY: Yeah, Merlin is really a central figure when it comes to understanding the relationship between Magic and politics in Britain. And that’s because, in various examples of imaginative literature from the Middle Ages, Merlin is imagined as this ideal royal advisor. So he’s the royal advisor, of course, to the court of King Arthur and he represents a particular type of person; someone of immense wisdom and occult learning who is able to increase the glory of the King, in this case, Arthur, by means of his access to secret knowledge. And so that kind of person does actually exist in British history. Merlin himself is a constructed person, you know, there isn’t one real person who, perhaps, lies behind Merlin but probably more than one real person, if we’re being honest about it. He’s constructed in the 12th century by Jeffrey of Monmouth out of these two main figures; one of whom was a bard of the old North, so of the Celtic old North known as Myrddin who goes mad after a battle and goes to live in the woods and there he communes with nature and he gains secret knowledge.

And the second person is known as Merlin Ambrosius and this is a boy who turns up in Nenniuse’s “Historia Brittonum,” a very ancient history of the Britons. And according to this story, Ambrosius is the boy who comes to the aid of King Vortigen when King Vortigen has got trouble with this castle. This castle seems to be falling down and Ambrosius is the one who says, actually there are two dragons fighting underneath your castle, a white dragon, and a red dragon. And they represent the white dragon as the English, the red dragon is the British and they’re fighting control of the island and he has these prophetic powers. Then what Jeffrey says is well you know these two people, the boy Ambrosius and Myrddin the Bard who went mad at the Battle of Arthuret, these are the same person and he constructs this whole persona for Merlin as Arthur’s advisor.

CC BY-SA (en:User:MykReeve)

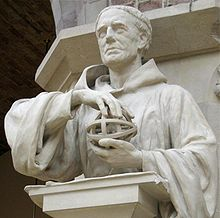

But in a way, that story is kind of beside the point. What really matters is that Merlin provides a pattern for real-life people. So if you take, for example, Roger Bacon. So in the 13th century Roger Bacon who was a Franciscan Friar man of immense learning, very interested in Magic, and very interested in the new sciences that are coming out of the Islamic world at this time, becomes a kind of royal advisor to Henry III. And so that’s the first time that we get a real-life person assuming the mantle of Merlin and there are others as well. But by far the most famous, that most people will have heard of, is John Dee who quite consciously sees himself as Merlin reborn and becomes the occult advisor to Queen Elizabeth.

AP: Yeah, can you tell us a bit more about the role of John Dee in British politics? I know that many people in the audience know John Dee very well.

FY: Yeah, I mean Dee is absolutely fascinating figure. He is somebody who is almost stranger than fiction, this is fair to say. But we know so much about him because he kept a detailed diary. This diary lay hidden until 1659. John Dee died in 1608, so it’s many decades after his death. His diary is discovered almost by accident and the diary reveals what Dee was really up to. That is to say, he was talking to spirits, talking to Angels. Today, I think, among occultists, particularly Dee, is probably best known as the originator of Enochian Magic. So that’s very strongly associated with Dee, the idea of angelic languages and angelic spirit conjuration. But he worked with a couple of scryers, most notably Edward Kelly and they did some extraordinary things, although it seems that Kelly also did lead Dee down the garden path. Quite a lot of time he seems to have been a rather Mercurial character. But yeah, I mean look, the important thing is that this stuff people didn’t know about during these lifetimes, so you have to be a bit careful.

But Elizabeth retains her trust in him and she shows that, when she becomes Queen on the 17th of November 1558, she immediately gets in touch with Dee and asks him to cast the horoscope for her coronation. In other words to work out what is the most propitious day on which she can be crowned and that happens in 1559. But that means that she is right from the beginning willing to take occult advice from him. However, I think Dee fancied himself as Merlin rather than Elizabeth necessarily fancied herself as Arthur, in the sense that she wasn’t always willing to take his advice. His influence over the regime changes through time and by the 1590s he’s been squeezed out. He’s obviously, got to compete with all these other people like Dudley, like Cecil who were all trying to get Elizabeth’s attention at this time. And yes he does have some influence and one of the key areas where he has influence is prompting Elizabeth to start some kind of exploration of North America which, in historical retrospect, is of huge importance. He encourages Elizabeth to send a fleet to examine some mysterious rocks that have been found in Newfoundland. He believes that they contain silver, in fact, they turn out to be completely worthless. But the point is that the precedent of England taking an interest in North America has been set.

And he also coins the phrase ‘British Empire.’ He tells Elizabeth your ancestor King Arthur because bear in mind the Tudors are a Welsh Dynasty. So they trace their ancestor their ancestry back to Arthur like, you know, all good Welsh people can trace their ancestry back to King Arthur. And so he says your ancestor King Arthur probably conquered North America. I don’t really have any evidence for that but just let’s just say he did, because that’s the sort of thing that King Arthur would have done, so you’ve probably got as much right to North America as the Spanish. So you should take them on. And of course, that advice to Elizabeth emboldened her to take on the Spanish, which is partially responsible for her foreign policy. So resisting the Spanish Armada but also chartered privateers like Sir Francis Drake who go out and rob the Spanish ships and this is the beginning of England’s rise as a great power in the early modern period.

So there are some respects in which his influence was very great indeed and all of this comes out of things that he was told by the Angels. The Angels that he saw in the crystal or rather Edward Kelly saw in the crystal and conveyed to Dee; they give him these instructions which he passes on to Elizabeth.

AP: And he was the one who coined the term the British Empire wasn’t it?

FY: Yes, that’s right, yeah. I mean certainly, the idea of empire was already there in the reign of Henry VIII but it had more of a technical ecclesiastical meaning in Henry the Seventh’s reign it meant that Henry believed like the Roman Empire, the Holy Roman Emperor, he had complete independence in the church and the power to do whatever he wanted and wasn’t subject to the control of the Pope, that’s what it originally meant. But then it’s Dee who extends the meaning to mean some kind of enterprise of exploration and colonial settlement beyond the seas. So that’s how we would now understand empire. And that’s something which really is invented by Dee, yeah.

AP: Yeah, that’s very interesting because I think that, especially here in the channel, we tend to explore usually more than the history of the esoteric thoughts and the texts and even the contemporary world from a more anthropological point of view but this is also quite interesting how esoteric thought and esoteric beliefs have influenced history, even to a very large degree. And can you tell us a bit more about Joan of Arc because you mentioned her in the book and I think she’s a very fascinating character?

FY: Yes, the reason why she’s mentioned in the book is because her death occurred during the Hundred Years’ War. The Hundred Years War, as I’m sure many of your viewers will be aware, is this long-running dynastic conflict both dynastic and territorial between France and England. In which England was, for a lot of the time, having the upper hand to the point that the French monarchy was really kind of being pushed into a corner. The English were in control of most of northern France, they were in control of Paris, they were in control of Gascony and Aquitaine all these areas of Southern France as well. And the Kings of England were claiming the Throne of France. What happens is that Joan of Arc comes from this obscure village, Domrémy. She’s just a teenage girl at the time when she receives visions. These visions were very interesting from a religious point of view because although Joan later constructs them, or later interprets them, as being very much visions from God, visions from Saint Catherine, visions from the Virgin Mary.

Her village was renowned for the fairy tree of Domrémy. So there’s this sacred tree in the village, which seems to have a less than Christian significance, perhaps you could say. And in fact, during Joan’s trial, when she is eventually captured by the Burgundians and handed over to the English, the accusation is made that she’s actually a Witch, that she’s actually in contact with fairies, that these aren’t saints at all. But she’s receiving visions from, you know, a non-Christian other-world if you like. So I think these are interesting complications to her case that she leads armies into battle, she inspires the French troops to victory over the English but she has eventually betrayed and captured and she’s put on trial for a number of different things. One of them is Witchcraft. But ultimately her conviction is secured for heresy rather than for Witchcraft and part of that is her gender non-conformity. So her refusal to dress in women’s clothes is seen as an act of heresy and she is burned to death at the stake.

Now that’s important in English political and legal history because she is executed under an English jurisdiction in Rouen. She is the first person that we know of in English history, with the possible exception of a lady called Margery Jourdemayne, although actually that that takes place a little bit later. So yeah, Joan of Arc would be the first that we know of in English History to be executed for Witchcraft by burning. That’s something which normally we would associate with happening in other countries, didn’t happen normally in England. Although having said that, this isn’t technically England, even though it’s under English jurisdiction. But there are many interesting aspects to this case but I think it’s certainly an example of the weaponisation of accusations of Magic, and accusations of Witchcraft in order to dispose of someone who is politically inconvenient. One of the accusations made against Joan was that she must be a Witch because at one point she was imprisoned in a castle and she managed to get out and part of that was by leaping over this chasm which is extraordinarily difficult to leap over and she managed it. And so one of the arguments was she must be a Witch because she did that. And another reason she was accused of being a Witch was that she used to receive holy communion every day if she could. And at the time that was not normal Catholic practice and so people said oh, she must be taking these consecrated hosts and abusing them for Witchcraft as she’s receiving them so often. So these are rather tenuous grounds perhaps on which is to say that she was a Witch. But yeah, nevertheless there are, yeah, some fascinating aspects to that story.

AP: Yeah, absolutely and this makes me wonder and you know, when does the shift between Magic, being a political weapon to Magic, being a political threat happens?

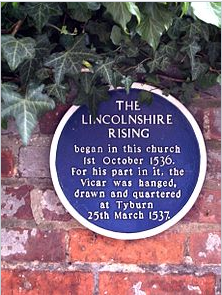

FY: I think the two things always go hand in hand. There are parallel developments really. I think that Magic doesn’t really have any political significance in England before the Norman Conquest. Even after the Norman Conquest for a long time, it has very little political significance and it’s only when we get to the middle of the 12th century, a period that we call The Anarchy when essentially you’ve got a dynastic crisis. Henry I dies, and his son William Adeling has been killed in this disaster known as the sinking of the White Ship. So the normal heir, the eldest son has gone down with this ship, he’s drowned, leaving behind a daughter. Now this is mid-12 Century England, and the thought of a woman succeeding to the throne of England at this time, to some is completely beyond contemplation, and one of those men is Stephen of Blois who is a relative of Henry I and he says right, I’m gonna just claim the throne, I’m going to say I’m the eldest male I’m going to take the throne. But the trouble is that in England there’s no law that actually says that a woman can’t succeed to the throne. So the Empress Matilda, who is only the first surviving daughter, also claims the throne and she has influential supporters such as Robert Duke of Gloucester – Earl of Gloucester, sorry. And Robert Earl of Gloucester commissioned the first known horoscope ever created in England and the purpose of that horoscope is to discover whether the forces of Stephen of Blois are going to invade England. So that’s really when we get the entry of Magic into English politics through astrology, interestingly enough.

And this is a pattern that’s repeated again and again, that a kind of weaponisation of astrology to find out, you know, whether there’s going to be an invasion, how long the King is going to live and things like that. But the thing about astrology is that while it can be regarded as something very positive, as a form of wisdom that enhances the King’s rule or in this case the Queen’s rule, to build up the reign. At the same time, it’s very easy for someone to come along and use astrology to ask the question how long is the King gonna live? And as soon as somebody does that then it’s got a dark side to it, that this could be a form of sedition. So I think what you see is monarchs, at one and the same time, they are trying to appropriate for themselves these magical powers and yet at the same time they are ruthlessly persecuting anyone who tries to use those magical powers against them.

Darkmaterial

So I think there are different inspirations that they draw on here. One of them is King Solomon, you know, if you look at the Old Testament, King Solomon is this king of great glory, great wealth, and great wisdom who, in the apocryphal tradition, becomes the commander of spirits. So think about titles of great grimoires like The Key of Solomon, and The Lesser Key of Solomon. The Greater Key of Solomon says Solomon is this figure credited with magical powers and yet he’s also this model of royal splendour. If you think about something like the Saint Edward’s Chair which is the throne on which the monarch is crowned. Less than a month from today King Charles is going to be crowned in that chair. If you look underneath it, first of all, you’ve got the Stone of Scone which is supposed to be the stone on which Jacob lay down and had his dream of angels ascending and descending on a ladder, which has been adopted by occultists for centuries as this image of the principle of correspondence – As Above So Below – the idea of celestial communication. And also next to the Stone of Scone the compartment that it sits in are two leopards, golden leopards and they represent the golden leopards that appeared on the Throne of Solomon.

And not only that but the chair is set in the middle of a magical sigil and this is the Cosmati Pavement that was created in the reign of Henry III and it was created by one of the… amongst the Westminster and it has an inscription on it to the effect that it is a microcosmic portrayal of the macrocosm, of the cosmos itself. And if you’re thinking about, you know medieval understandings of natural Magic, and astral Magic, the purpose of this magical sigil is to act rather like the naval of the world that was created in the middle of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. It’s a symbolic centre of the world onto which the rays, the celestial rays, the influences of the planets will be drawn at the moment of coronation and that’s the reason why coronations have got to be astrologically determined, you know. And that’s still true in Elizabeth the First’s reign, that it’s astrologically calculated. Whether the current coronation has been astrologically calculated I don’t know but certainly there used to be, that was considered very, very important. So all of those are, you know, obvious ways in which monarchs were drawing upon magical power and yet at the same time if anybody tries to come against the monarch with Magic they are smeared, you know, as an evil magician, as a Witch, as a necromancer and punished accordingly.

CC BY J. Paul Getty Trust

AP: Yeah, that’s a good point. So Magic has as a weapon and Magic as a threat always go hand in hand, in a way. You don’t have a shift from one to the other.

FY: Yeah, I think that’s very true but I think that there are certain shifts that do take place. I mean one of them is the Reformation. So at the Reformation, you’ve got a transformation in the way that people view Magic. Certainly, the idea of Witchcraft as it was understood in the 16th and 17th centuries, what we might call malefic Witchcraft, which is Witchcraft understood as a purely evil act that involves some kind of pact with the Devil. You know, this understanding that the Witchfinders have, that’s something which doesn’t arrive until the 16th century and so the idea that Magic becomes significantly more threatening as a result of the Reformation and also traditional beliefs, normal sort of Catholic beliefs, by the mid 16th century those have been demonised by the Protestant reformers. Those have been vilified and portrayed as a form of Magic in themselves. So the category of Magic has been broadened enormously in the 16th century. Things that would have been considered normal are now deemed superstition, they’re deemed to be magical practices. And not only that, but the sense of threat has massively increased and so the level of paranoia, the level of official paranoia that you’ve got in the 16th century is like nothing that you’ve seen before.

AP: Yeah and what do you think? How did it evolve throughout those times, throughout the 16th century? The perception of Magic and its role in political history?

FY: Yeah, I think that there are many strands to this but one strand is that the House of Tudor sees itself as Arthurian. Bear in mind that Henry Tudor, Henry VII, the guy who defeats Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, he names his eldest son Arthur. Now, as it happens that the eldest son doesn’t live, he dies shortly after marrying Catherine of Aragon and it turns out to be his second son who becomes Henry VIII who actually succeeds him. But Henry VIII, as well, is obsessed with Arthurianism. He has this round table created. Henry VIII is very reliant on the predictions of astrologers, they have court astrologers who could be said to be figures taking on the mantle of Merlin. None of them rises to the kind of same level of greatness as John Dee but certainly, they are, you know, significant figures at those courts. But then the Reformation really strikes in a big way in Edward the Sixth’s reign. So the young son of Henry VIII, who was only a boy when he comes to the throne, dies at the age of 17 of tuberculosis and has this short but very, very radical reign where there’s an attempt to impose a very puritanical form of Protestantism on the kingdom, like nothing that would be seen until the after the Civil War in the 17th century. And it’s during that time that any kind of Magic, any superstition, any practice that could be seen as popish, as Catholic is vilified.

Elizabeth rows back on that I think Elizabeth is a slightly more tolerant character and perhaps not as tolerant as she is sometimes portrayed. She wasn’t a particularly tolerant woman but she did have slightly more interest in maintaining the peace between her subjects than some of her predecessors. And so she really goes to a position in 1563 with the Witchcraft Act where she’s interested in only criminalising acts of harm by Witchcraft or an attempt to kill someone by Witchcraft. If you contrast that with Scotland, Scotland undergoes this much more puritanical Reformation. There any kind of superstitious act could be Witchcraft and you could be put to death for it. But you can only be put to death for Witchcraft in England if there’s sufficient evidence or the judge is sufficiently convinced that you have tried to kill someone or you’ve tried to harm someone. But, for example, that leaves out things like love Magic. So love Magic is not necessarily illegal, it leaves out things like, you know, Magic to predict the future, you know, kind of fortune telling and things like that. It leaves out, you know, treasure hunting, for example, by Magic. These things are not necessarily considered crimes. Or Magic to, you know, reduce pain in childbirth which is very, very common.

But having said that, those things remain offences according to the church. So you can still be you know hauled up before an Ecclesiastical Court if you do those things. A difference is the Ecclesiastical Court can’t put you to death, it can only publicly shame you – is the worst that can happen to you. So yeah there is an evolution towards taking a much harsher view of Magic. And not only that but of course, before that act, before 1563 Magic had not been criminalised, it had not been against statute. So throughout the Middle Ages, you weren’t actually breaking the law if you did Magic. But you could be pulled before a church court and you could be publicly shamed and ostracized and all these things.

The only situation in which Magic was a crime was if it was directed, in some way, towards the king or the queen. So political Magic was always a crime and that’s because there was an old statute the 1352 Statute of Treason which, incidentally, is still enforced in Britain today. And one of the things that say is that if you compass or imagine the death of the king you were guilty of treason and compass and imagine would include things like magical intent. If you have the magical intent to kill the king. If, for example, you create an image of the king in order to destroy the king via sympathetic Magic that would be compassing and imagining, therefore you’re guilty of treason. So that form of political Magic would have always been illegal but things really intensify in the 16th century.

AP: I’ve always had a personal fascination with the figure of Anne Boleyn. So obviously, I want to know more about that and I want to know more about the story of Anne Boleyn and her connection with Witchcraft. I think she was also accused of being a Witch, so yeah, tell us more about Anne Boleyn and Witchcraft because that also interests me.

FY: Yes, I mean this is a fascinating case. I mean it’s probably the most prominent example of the political use of accusations of Witchcraft -certainly from Henry the Eight’s reign. It’s one of many accusations that are made against Anne Boleyn. So there’s a massive charge sheet that’s very hastily drawn up against her in 1536. And the main charge and the charge on which she is executed is incest as treason. The idea that she has been sleeping with her brother. That obviously is treason as understood at that time that, you know, if you’re the king’s wife and you’re committing adultery then, you know, that in itself it is a form of treason, in addition to, you know, the connotations of incest as a crime against nature and so forth. But thrown on top of that is Witchcraft. Now that accusation of Witchcraft isn’t brought forward, it’s not taken forward to the trial, it’s not one of the main accusations on which she is convicted. But it’s very interesting that it’s thrown in there and one reason why it is thrown in there, we encounter this a lot in Henry’s reign is if someone is guilty of treason there’s a belief that they are the most depraved person that could be imagined. That treason is the supreme crime – there could be no worse crime than wanting to kill Henry VIII apparently. And so, if you are guilty of the worst possible crime that anybody could imagine, that means that it’s not much of a stretch of the imagination to imagine that you could be guilty of all sorts of other horrible crimes. So why not just throw them in there? You know, why not just throw in Witchcraft because that’s a horrible crime isn’t it? And so there’s an element of, yeah just throwing it in for the sake of it in order to smear somebody’s character.

I think the fact that she’s a woman is very important, there’s a strong element of misogyny in accusations of Witchcraft. It’s not necessarily an accusation that would have been made against a man. But I think when you look at the cultural influence of it, Catholics in Elizabeth’s reign looked at this accusation and they said, oh your mother was a Witch and there was this belief at the time that Witchcraft was hereditary. So therefore there’s a kind of insinuation amongst Elizabeth’s enemies, the Catholics, that Elizabeth is probably a Witch because her mother was a Witch. And it’s at this time that the myth grows up that Anne Boleyn had six fingers on one hand. But the evidence suggests, and historians have looked at this exhaustively and all the evidence points to, that being entirely a story that was made up in about 1580. It’s long, long after Anne Boleyn died. There’s no evidence of it in any of her paintings or any physical descriptions of her. But there was this belief that you know if you’ve got a physical deformity, particularly if you’ve got an extra appendage on your body. An additional appendage on your body, which is like a flap of skin or an extra finger or a nipple where it shouldn’t be or something is the Devil’s Mark. And that’s where the Devil will come along and suck blood from your body thereby cementing the demonic pact. And so I think there’s a hint of that in this accusation that she has six fingers on one hand.

But anyway, there’s this sort of retrospective attempt to claim that Anne Boleyn actually was a Witch. But it’s not really about Anne Boleyn, it’s really about trying to discredit Elizabeth. And there’s, you know, some of her Catholic enemies even tell stories about Elizabeth’s being able to walk through walls showing that she therefore must be a Witch. And of course, the fact that Elizabeth never gets married, immediately, you know provokes these, you know, hostile figures to see her as an unnatural woman and therefore she must be a Witch. And so you get this whole cauldron of misogyny going on, which is directed both against Anne Boleyn and also against Elizabeth.

AP: Yeah, I was about to ask in your research about the history of how Magic intermingled with politics, do you find there is a difference in gender, you know, how the role that men who are practising Magic played, as opposed to how women were seen?

FY: Yes, there is very much a difference and I think this is quite a profound feature of the way in which male and female magical practitioners are treated in the early modern period. And I think one difference is that when women are engaged in magical practices they are seen as being, in some way, one and the same as the magical practice, that it arises from their nature and therefore it’s bound up with these, you know, misogynistic beliefs in women being more easily tempted by the Devil, grounded in, you know, the story of Genesis – Eve being the first to be tempted and so forth. Whereas when men are engaged in magical practices usually they are perceived as being more learned and therefore they’ve committed a crime but that crime is not what they are. So therefore when a man does a magical act, he might be called a Witch, I mean which is a gender-neutral term at this time, but the chances are that he won’t. Chances are he’ll just be said to be a Sorcerer or he’ll be said to be a Necromancer and these are not terms that have quite the same level of slur attached to them as Witch. As soon as you call someone a Witch you are saying that they are bad through and through, that they have given themselves entirely to the Devil, that essentially they’re worthy of death. You know, Exodus: Thou shalt not suffer a Witch to live, is the key verse for all these witch-finders, all these judges who are keen on rooting out witches and women almost always, you know, if they’re engaged in some kind of magical act they will be called Witch. And so there’s a sense in which the practice of Magic is far more deadly for women than it is for men. Because there’s a chance that a man might be pardoned, there’s a chance that he might be seen as you know a learned man who just went a bit far, who was a bit misguided, who committed this crime whereas with a woman she is more likely to be called a Witch and therefore she’s bad through and through and there’s no escape from that.

AP: That’s a very interesting argument. I had never thought about it. I mean the matter of the identity, I guess, that’s very interesting, how a Witch, when it’s a woman, is believed to be her nature whereas for men it’s more something they’ve learned. That’s very interesting. I was thinking, yeah, I guess it was going through my mind, is that I guess that in history, things, most things, have been more difficult for women as opposed to men. So I was wondering whether there was something specific about Witchcraft and Magic that would make it worse or maybe it was, in this case, Witchcraft and Magic just part of the general misogyny or do you think there is something specific about Magic that emphasizes, even more, the misogynistic aspect that was already there in the culture.

Richard Croft CC BY-SA

FY: I think when it comes to political Magic, political Magic can come from the lowest of the low, you know, it can come from the most marginalised in society. Well, there’s one great example; during the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536, when Henry is up against the people of the North of England who are rebelling against him for dissolving the monasteries. And there’s this woman near Hull who starts a magical fast against Henry VIII the idea being that if she correctly fasts and follows these ritual procedures then Henry will die. And she was very poor, you know, a kind of landless peasant woman and that was considered a threat, you know, that you this poor woman was doing that.

But at the same time you got court Magic, you know, this is a very important aspect of political Magic and it is women at the court who find themselves in an immensely vulnerable position. In the vast majority of cases, they owe their status to their marital status. So they don’t have any position at court except through who they happen to be married to at the time or whose mistress they happen to be at the time or through whose mother they happen to be at the time so their status is acquired by their particular relationship to a man. And this means that women in court might be more willing to make use of Magic to secure their position. And there are cases of this where women were essentially trying to use love Magic, for example, to make sure that they secured the affection of their husband or their lover. You’ve got examples of women trying to predict when the king might die to see when their child might be in the line of succession and when their husband might be in the line of succession. And so there are, yeah, there are both women at the top and the bottom of the social pile who are getting involved in political Magic.

But you know for slightly different reasons, you know, whereas for women at the bottom of the pile, this is an act of desperation because it’s the only thing that they can do. For women who are at the top of the social pile, this is one technique among many. Because, of course, if you’re at court it’s not just Magic that you’ve got at your disposal, you also have powers of persuasion or powers of seduction potentially. So there is this, you know, a battery of tools that royal women or aristocratic women can use. But certainly Magic is one possible one.

AP: That makes me think about the argument about Witchcraft being very often a tool for those who are at the fringes of society. Did you find in your research that is true? Because it seems that there are also Magic practitioners that had a high status. So how do you in your research… what is the relationship between the different status that people have and their engagement with Magic? Is the prevalence of those in, you know, at the fringes of society or that have less power, is there a difference, you know, between how people with power engage with Magic as opposed to people who lack power and want to gain some?

FY: Yeah that’s a really interesting question. I think that when it comes to political Magic, specifically, you’ve got people at both ends of the spectrum, as I’ve said. When it comes to Magic, more generally, I think yes, generally it is something which is a resort of the powerless. Naturally enough because there aren’t many forms of power that you can exercise in a rigidly hierarchical society, that subverts that hierarchy, other than Magic. But Magic gives you access to much greater Powers. So, you know, you’ve got access to angelic power, access to demonic power or access to you know the power of the Fairy, there is a great deal of Fairy conjuring that’s going on at this period as well, in the 16th century. And that allows people to yes, assume a power that they wouldn’t otherwise have.

I think that yeah when it comes to political Magic it can be those who are quite close to power who are using it but not usually while they’re in the ascendant. So if you think of the image of the wheel of fortune which is often deployed to describe life at court in the 16th century and indeed earlier. Those who are at the top of the wheel, they’re not going to need to use Magic. So there were accusations against Cardinal Wolsey, when he was at his zenith of power, that he had a magical ring that was keeping Henry the Eight’s will captive to him but the reality is he didn’t need a magical ring because, you know, Henry was completely reliant on him emotionally and politically. And similarly Thomas Cromwell, you know, there were similar rumours about him. But I think that that just comes from the sheer randomness of Tudor Court life. People couldn’t get their heads around on, you know, why this guy’s fallen, this guy’s now you know at the top of the pile. Why is this? It must be down to Magic. So I think that those people weren’t using Magic. But then, on the other hand, quite influential figures when they fell from grace sometimes they would find themselves using Magic.

So Lord Hungerford is a good example. He was a key ally of Thomas Cromwell. He was involved in securing Henry the Eight’s marriage to Anne of Cleves. Now anyone who knows about Henry the Eight’s six wives will know that Henry was dissatisfied with Anne of Cleves. He thought that she wasn’t pretty enough and he refused to consummate his marriage with her and essentially kind of divorced her, although didn’t tell her in this case. And so yeah, essentially that’s the reason why Thomas Cromwell loses Henry’s favour and the same with Lord Hungerford. But Lord Hungerford resorts to Magic. So he tries to win back Henry’s favour by Magic and that results in his execution.

So yeah, there are examples of people pretty close to the top who are using Magic to try and gain their will but normally, when they fall from grace. So I think to that extent Magic is a tool of the powerless. But it’s also, yeah, it’s one of the tools that are available to those who want to challenge the status quo. There are also lots of examples of rebels who plan all sorts of insurrections, rebellions, uprisings, you know, plots of assassination and so forth Which have a purely material element to them but they also make a magical pact or summon a spirit to prophesy what’s going to happen, whether it’s going to be successful, or they cast the king’s horoscope and things like that. And there, I think it’s more of a kind of belt and braces thing that, you know, yes they’ve got this plan to assassinate King but let’s just summon a demon and you know find out what the spirit world has to say about this as well, just in case. So I think it can play a variety of different roles.

AP: Yeah, and I was thinking, from your research, what does appear to be more prevalent, the thought that people inherit Magic, that Magic is something that you actually have or do not have naturally? Or is it something that you learn?

FY: Again, I think this is very gendered. I think when it comes to women there is this perception of inherited malice, of inherited Witchcraft and a very good example of that when it comes to the political sphere, is Jacquetta of Luxembourg. Jacquetta of Luxembourg is the mother of Elizabeth Woodville. Elizabeth Woodville becomes the wife of Edward IV and accusations were levelled against both Jacquetta and Elizabeth Woodville of Witchcraft. Accusations that are later revived by Richard III who wants to claim that Edward V, the son of Edward IV, is actually illegitimate because Elizabeth Woodville deceived him into marrying her by Witchcraft, which would mean that the marriage was invalid, which would mean that Edward the fifth is illegitimate, which would mean that Richard III, surprise, surprise becomes king. So that’s one of the arguments that Richard uses in 1483 three and I think there’s this deeply kind of misogynistic perception that women pass on the badness, you know, down the generations.

When it comes to men I don’t know of any examples, that I can think of, where that similar idea of inherited Witchcraft is applied to men. When it comes to men it’s all about, you know, this person has the learning or required, the right books or acquired the right magical equipment and therefore has this ability. On the other hand, we do encounter the idea that some men have a greater aptitude for communication with the spirit world than others. So Dee, for example, can’t, most of the time, see anything in the crystal. There are a couple of times when he does but most of the time he has to rely on these guys; Barnabas Saul the first scribe that he has and later Edward Kelly. So there is certainly this idea that you need a medium and also a use of children as mediums by male magicians. There’s a very widely known scrying experiment where the magician covers his thumbnail in oil and then gets a small child to look into the thumbnail, for a very long time, until the child sees the future. And so that’s a kind of basic form of scrying but it has to involve a child who interestingly can be male or female, doesn’t matter whether it’s a boy or a girl but it’s the idea that innocence preserves the ability to make contact with the spirit world. But yes, I think it is deeply gendered when it comes to the idea of inherited magical ability.

AP: And do you think that there’s also a bias towards whether Magic is beneficial or not? I mean have powerful monarchs been served by female magicians or was it just men? And also I guess that it was a general question. So first I was wondering whether, when Witchcraft was attributed to women, it was always negative, always harmful and second, when it comes to Magic used by powerful people like monarchs, for instance, where they always relied on male Sorcerers or Magic practitioners or are there also female?

FY: There are a couple of examples of female magical practitioners who serve monarchs. One was Millicent Frankwell who was the personal Alchemist to Elizabeth I. Probably the reason why Elizabeth chose a female personal Alchemist is because the role of the Royal Alchemist is actually quite an intimate one, in that the Alchemist was not just responsible for the idea of producing gold for the monarch but also for producing iatrochemical medicines. So that is to say a kind of chemical physician who would produce these potions to prolong the monarch’s life and in the case of Elizabeth, she actually had these alchemical operations happening quite close to her personal chamber. And in fact, Elizabeth herself was an Alchemist, she did engage in these alchemical experiments. So it may be that it was a matter of propriety that it had to be a woman who was doing this. But unfortunately, we don’t know very much about Millicent Frankwell.

The only female Royal Magician that we know a great deal about was a lady called Mary Parish and she was an extraordinary woman who became one of the royal Alchemists to Charles II. But she worked under the senior Royal Alchemist who basically wasn’t as good as she was and stole her ideas and you know, made use of her experiments and also sexually assaulted her. So she did not have a positive experience of being a Royal Alchemist. But she was briefly a royal Alchemist and then she became the sort of spiritual advisor to a man called Goodman Walter who was First Lord of the Admiralty at one point, so quite an influential figure at the court of Charles II and then James II and then William and Mary. So there are a couple of examples of women magical practitioners being involved but on the whole, it tends to be men.

AP: And what about the perception of Magic-connected women? Is it always harmful when it is performed by women and considered more positive when performed by men?

FY: Not always harmful, no. I think that there was general recognition within the population in the 16th and 17th centuries that there were such things as white witches, although that term is a little bit misleading and wasn’t often used at the time. The term that I think a lot of scholars prefer now is cunning people, cunning folk, cunning women, cunning men or service magicians. So that is to say those who are professional magicians and actually dealt with people. They were consulting magicians essentially that would deal with things that you needed corrected in your life that a magician could help you with. And they did engage in a kind of primitive form of psychotherapy one could argue. So one of the key things they dealt with was finding lost items, finding out the identity of thieves, basic love Magic and things to do with fertility and reproduction. So women were very often involved in that, lots and lots of cunning women.

Only a tiny handful of cunning women were ever convicted of Witchcraft. This is very interesting because you’d expect that maybe they all might have been suspected of Witchcraft but it seems that the population at large needed these people. You know, they performed this very necessary role within society and therefore they generally are, you know, taken out of that category of the sinister magical woman who is a Witch. So yeah, there is an acceptance that women can engage in positive forms of Magic. In addition, you’ve got, you know, the handful of women Alchemists as well. So it wasn’t exclusively negative but I would say that it was certainly more dangerous for a woman to engage in magical practice in the 16th and 17th centuries than it was for a man because she immediately put herself at risk of that suspicion of Witchcraft. Whereas for a man, yes there were risks, you could be tried for engaging in Necromancy and Sorcery but the chances of being executed for those crimes were significantly lower.

AP: That’s very interesting and I guess as a final question I’d like to ask you, in the centuries that you have covered in your research, how has the perception of Magic changed? You know, in terms of whether has it changed from one century to another and how it has evolved?

FY: Yes, I think that there are significant…

AP: In relation also to politics and the power that it exerted on society, I guess.

FY: Yeah, absolutely there have been significant changes. I think that when it comes to the difference between the Middle Ages in the Early Modern period there’s, perhaps, less change than you might expect. It could almost be called one of the constants that holds together the late medieval world and the early modern world that Magic continues to be feared, Magic continues to be something that monarchs try to make use of whilst also at the same time pretending that they’re not making use of Magic and saying, you know, Magic has got nothing to do with it. A good example of that would be ‘royal touching.’ So there was a practice of kings and queens who would touch people suffering from skin diseases that they believe were magically cured. But they would insist this is absolutely not Magic, what we’re doing this, you know, we’re just saying a prayer and it’s happening, you know, automatically – so Magic.

But yeah, you’ve got these claims, you know, continuing. I think that one change that happens is that the Reformation makes it imperative that those in power aren’t seen to be doing things that are Magic, even if they still are. I think it also leads to greater paranoia when it comes to Magic but then after the Civil War, after the interregnum, the period where England is briefly a republic, Charles II really changes the tone. Now I wouldn’t want to suggest that Charles II didn’t believe in Magic, we don’t really know what he thought about it, but he certainly didn’t want Witch trials happening. And the reason he didn’t want Witch trials happening if they could possibly be held, was that he saw it as a sign that he wasn’t quite in control of the nation if the Devil was running wild and causing people to become Witches and causing havoc in the countryside. That meant that the health of the nation was not great and he, as the restored King, needed to show that the health of the nation was great and therefore he was against the idea of Witch trials. And that’s really where the decline of a connection between politics and Magic begins, in the reign of Charles II.

And then after the Glorious Revolution in 1688, when James II is overthrown for being a Catholic, and replaced by his cousin William of Orange, we get a situation where the elites, that the new elites start to construct themselves in terms of being hostile to superstition. And part of the reason for that is that James had been a Catholic. Catholicism was intimately associated with superstition and therefore the less superstitious you could show yourself to be the more loyal you could show yourself to be to the new regime. You get a group of people called Whigs who are dominant in British politics and Whigs come to be associated with these sort of proto-scientific ideas that are in circulation and therefore you get this kind of performance where people are saying, you know, I’m not superstitious, I don’t believe in this stuff or I don’t put much store in this stuff, it doesn’t really matter. Now that’s purely the elites, it doesn’t really filter down very much to ordinary people on the ground but of course, what matters for the way that politics is conducted is the way that the elites conduct themselves and how what they think is important and therefore the idea of Magic really falls out of the discussion of politics.

And I think that in the 18th century, if you’d raised the idea of Magic in politics, people would have laughed at you and yet there is a sense in which it comes back in the 19th and the 20th century and particularly in the 20th century. When we look at some of the things that happened during the second world war, where really it’s as though that shadow of Magic does make a comeback but perhaps that is something for a whole other extra show? I don’t know.

AP: Yeah, definitely. And I was thinking that you know, is it possible that Magic is seen as it’s all of the powerless just because the powerful don’t say that they use it? So it seems like the powerless are the ones who resort to Magic but actually the powerful ones, just do it in secret.

FY: I think that’s a very astute observation. I think that if you are powerful then you control the discourse, you control the language that’s used and so you can redesignate what you’re doing as not Magic and so a good example of that would be the Royal touching. If you are controlling printing, if you’re controlling communication, you can say this is not Magic even if it’s Magic. You can say, you know, what happens at the coronation is not Magic even though, you know, it looks to most people like something, a magical rite of some kind is taking place. And so yes, I think you’re absolutely right, it is Magic is something which is done by the people you don’t like or it’s something that’s done by the people that you want to persecute, very often. And yeah, it’s like Witchcraft. Magic is a word that we use to discredit those we don’t like.

AP: Yeah, in religious studies we tend to say that Witchcraft has been often used as a term of othering. So a term used to other practices that are not accepted. So yeah, that makes sense. Thank you for thank you for that. I think it’s good that we had this as a final note because I would imagine that lots of people would have had questions of that sort because there’s also a certain narrative about powerful people that engage with Magic. There was definitely, like a few decades ago I think, even in Italy, this Freemason Lodge of which Berlusconi was part of, and other politicians and powerful people in Italy that, you know, also gave the impression to Italians at the time that powerful people were engaging with Magic to stay in, you know, in a place of power. So yeah, but it’s interesting because it tends to appear to the public more as though people that are on the fringes or that are powerless – engaged with Magic. But then perhaps, that doesn’t necessarily reflect the reality, it reflects more who is in control of the narrative and who is the subject of the narrative around Witchcraft.

So yeah thank you so much, Francis, for coming over to the show. It was a super interesting conversation and I definitely invite all of my viewers to look in the info box where you will find the link to Francis, Dr Francis Young’s books. And not just one that we mentioned but also the other two ones, another one on politics as well. And “Twilight of the Godlings.” I like the title by the way. I like your titles and your books. I haven’t read yet the Twilight of the Godlings but it sounds like the subject of a potential new interview if you’re willing to come over again.

FY: Indeed, yes.

AP: So thank you, thank you again so much. I really appreciate you coming over here and I hope you had a good experience.

FY: It was, it was very enjoyable, thank you very much.

AP: And thank you to 1ohisee and Craig for appreciating our interview and thank you to Andrew, João and Edward for moderating the chat.

So yeah, I guess we can wrap up. Thank you again, Francis, I really appreciated you coming over to Angela’s Symposium.

FY: Thank you.

AP: So thank you so much, guys, for coming over and joining us in this chat. And if you are watching this live or if you’re watching this later if and if you like this interview, which I hope you did, because it was super interesting – don’t forget to SMASH the like button, subscribe to the channel, share this video and all the other videos on Angela’s Symposium around with friends and family and everybody who’s interested in the academic study of Magic and Esotericism.

Also please consider supporting my work on PayPal or Patreon or joining Memberships or buying my merchandise. You’ll find everything in the info box and in a pinned comment and I hope you stay tuned for all the Academic Fun because there are lots and lots coming next.

So bye for now.

About our guest

Dr Francis Young is a historian of religion and belief who teaches for the University of Oxford’s Department for Continuing Education and is the author or editor of 20 books including Magic in Merlin’s Realm (2022) and Twilight of the Godlings (2023) https://amzn.to/3ZJOieS

Most relevant publications:

Magic as a Political Crime in Medieval and Early Modern England: A History of Sorcery and Treason (Bloomsbury, 2017) https://amzn.to/3zBpmLX

Magic in Merlin’s Realm: A History of Occult Politics in Britain (Cambridge University Press, 2022) https://amzn.to/3Kv8cpr

First streamed 8 Apr 2023

Twitter handle: @DrFrancisYoung