Dr Justin Sledge JS: Thank you. All right everybody, welcome back to the second round of German curmudgeon against the occult. Adorno’s Theses against Occultism. Which is, I think, an interesting text. And is also, as Dr Puca pointed out last time, a deeply flawed text in many ways as well. And so I think that’s interesting that we can pick up what’s interesting about it but also diagnose what’s really flawed about it. But Dr Angela Puca, from Angela’s Symposium, thank you for coming back, braving to come back with me after my power failed and everything else last time, but thanks.

Dr Angela Puca AP: Oh well, that was fun you know that’s the what happens when you are live, you have to be prepared for everything, but I thank you for having me on your channel, Justin, it’s always a pleasure or Dr Sledge.

JS: Whatever. Yeah, I’m glad you came back because this text is tough and it’s complicated and I’m looking forward to getting back into it. Any sort of thoughts from last time or if you want to try to summarise what we did last time or just any sort of thoughts to bring us back to where we were before we pick back up?

AP: Yeah we went through the first and part of the second thesis, I think, and one of the things that I pointed out is that there isn’t really a clear definition of what he means by Occultism when he talks about the theses against the Occultism. And I find it interesting that one of my Patrons suggested, and I think he was right, and then I found the paper, that if you want I can share, on specifically these texts and Adorno’s view of the occult. And Andrew, the Patron that I was referring to, he pointed out that perhaps what he meant was mass Occultism, the pop culture type of cultism. So not the Occultism that Aleister Crowley or other esoteric practitioners would engage in.

So I think that that’s correct and it mirrors what I then found in a paper published by Oxford University Press that’s called “Popular Occultism and Critical Social Theory: Exploring Some Themes in other Critique of Astrology and the Occult.” And this paper pointed out… oh sorry, I didn’t say the authors Nederman and Goulding or Wray Goulding. I never know whether it’s two names or two surnames, so sometimes it’s confusing. But it’s a bit of an old paper from 1981 and for people who are interested and have an academic affiliation they can find it on JSTOR but yeah, I think that confirmed the idea that when Adorno talks about Occultism he talks about pop-occultism. So what he’s presented in pop culture and what is consumed in pop culture and it made sense even when Andrew, my Patron, suggested that I thought, oh yes, of course, it makes sense in relation to Adorno’s philosophy because he’s very critical of that aspect specifically and you know how pop culture becomes a form of consumption. So yeah, what do you think about that?

JS: I think that that has to be right at some level because it makes sense that he’s, you know, it’s part of his broader critique and so if he’s critiquing doo-wop as a piece of popular culture he’s also going to be targeting pop-occultism. Now I think the question that becomes more interesting is to what degree that non-pop-Occultism, I don’t know what that would be, but non-pop-Occultism has become pop-Occultism now and to what degree Adorno’s critique.

AP: Elaborate, what do you mean?

JS: I mean there’s a moment where I don’t know, Alistair Crowley shows up on a Beatles album, like are we now getting into pop-occultism right, or like WitchTok, like are we getting into a world in which …

AP: That would be what Christopher Partridge calls “occulture” and I would say that that’s different from pop-Occultism. So occulture is more when you have occult themes that permeate pop culture whereas pop-occultism, I would say, that it is you know like the type of Astrology that you find in magazines as opposed to the Astrology that is done by esoteric practitioners that are really invested and really knowledgeable and utilise their astrological knowledge for esoteric purposes and have a certain worldview that accompanies that. I mean there is a difference between the person that just reads what the astrological forecast is for Aquarians or Leo people and just because it is something fun and it’s something that they half believe in, because it is, in a way, it’s not really a game but it is a form of entertainment that people half believe in. But that’s very different from somebody who studies Astrology, I don’t know, for 5, 10, 20, 30 years and they are deeply invested in that and perhaps they use Astrology to design certain ceremonial practices and it is an integral part of their tradition.

So you cannot just lump the two together, so and you can also not lump together the kind of pop-occultism, which is one of the random people that looks up astrological forecasts in the magazine, and occulture which is the actual Occultism that permeates and influences pop-culture like, for instance, musicians are influenced by Aleister Crowley or even Voodoo practices or demonology or demonolatry. I think that those are all different categories so I would say that on one hand we have Occultism and I know the contemporary scholars now prefer to use ‘esoteric’ practices because Occultism has a negative connotation but we can use that instrumentally because that’s the term that Adorno uses. So we have on one hand Esotericism and on the other hand, pop-occultism, which is what, probably, Adorno is actually criticising and occulture, using the term used by Partridge, a scholar who had a publication on that which is more the intersection between Occultism, the first category that we talked about and pop culture and how the first influences the other and in a way they can influence each other but it’s more the intersection between the two.

JS: Right. And that’s, I guess, what I would say is that I wonder to what degree … One I would see them as a spectrum, I suppose, is in the same way that one could criticise the categories of high and low magic or something like that, the way that folk magic and high magic have been criticised as distinct categories as rather than on a spectrum of practice and so I guess what I would suspect is that there’s much more of a dialectic between the two and that that there are more of on a continuum than they are two separate categories in my mind.

AP: Yeah, they can be like Venn diagrams, in a way. So there are places where they can meet but they are still distinct categories, I would argue. And the reason why I would argue that they are distinct categories, even though they may overlap in some cases, but more as in a Venn diagram rather than something that is actually the same thing. I would argue that they are distinct categories because I think that by lumping them together we tend to flatten the complexity and the nuances. And since the complexity and the nuance here is a massive part of what people actually do and what occultism is really about, that would just lead to misunderstanding it, to begin with. So, for instance, here when Adorno talks about the theses against Occultism and it doesn’t clarify what he means by Occultism, but I mean I agree with that paper and with my Patron who suggested that it’s about pop-occultism but the fact that he is not clarifying and lumping everything under the label it is just basically fostering misinformation and misunderstanding over what he is even against. It’s not clear, he doesn’t clarify that.

JS: Do you think these critiques and we’ll get into them further, do you think these critiques would also just apply, like do you think there’s any world in which Adorno is going to be open to any form of Occultism, whether it’s pop-occultism or like the most …?

AP: No, and I think, to me, he’s a very depressing guy. He knows what he doesn’t like but it’s not fully clear what he wants.

JS: Oh, he definitely I mean it’s just he wants 12-tone, atonal Arnold Schoenberg music and that’s the only music that really matters anymore, everything else has been has been sublated and we are now in the days of … I mean he writes music, I mean he can tell you what kind of music he thinks is like the superior music and this is a funny criticism that people often get of Adorno is that they say, oh he only says what he doesn’t like, he never says what he does but he constantly says what he likes. It’s just that no one likes that.

AP: Oh okay,

JS: It’s just that he’s a radical elitist and that he has a very progressive, progressive in the sense that things are on a progression and he thinks that high culture, the sort of post-bourgeoisie high culture actually, absolutely is a superior culture and period. I mean so, it was just which is a very funny thing because he’s certainly not bourgeois he’s more aristocratic in a certain kind of way and yeah, I’ve never gotten the critique that he doesn’t know he never tells us what he likes. it’s just that no one likes a three-hour-long Symphony where there’s no resolution.

(laughter)

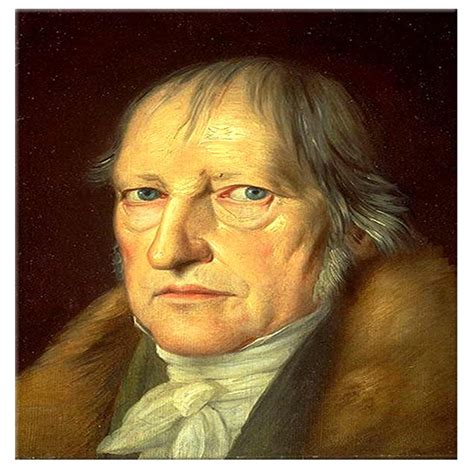

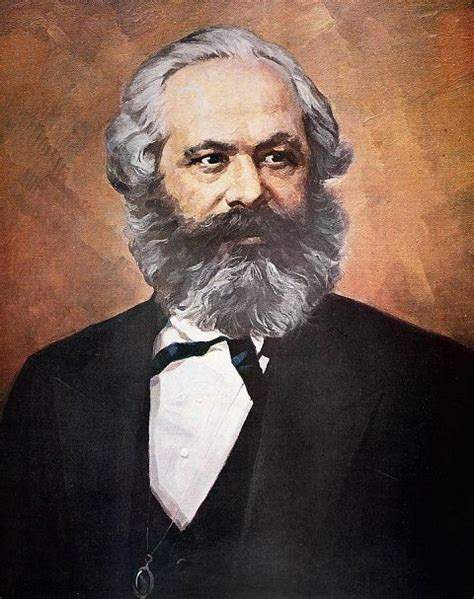

There’s, I guess, some who people do, graduate students in music theory I suppose. But I guess there are still people out there who really do believe that that is still the apex of western music so far. But it just feels like a three hour long panic attack to me. But maybe that’s the 20th century, what maybe that just is what the appropriate historically, developmental music is when you’re in 1947 – it’s just a three hour long panic attack. So I guess the other thing I’ll say, before we jump back into the theses, is that this kind of document is just going to fall flat for anyone who’s not already basically on Adorno’s wavelength and that is a very peculiar kind of historical materialism and it’s a historical materialism where Adorno has had to come to the fact that there is no linear progression to history, that history is moving but it is not moving in any given direction and that the laws of history, discovered by Marx, as much as you want to believe that they’re there or not, he thinks that they’re still driving history, he just thinks that they’re not driving it anywhere. And that this has become this is a rather horrifying situation because you have all of the historical determinism of Marxism but none of the hope that that it’s going to resolve itself. Again this is a Scherbergian kind of Marxism but none of the hope it’s going to resolve itself.

In fact, I think Adorno basically believes, and this is the point that was raised by Benjamin, it just as well could push itself all off a cliff and that is probably what’s going to happen. He just says look, no one ever saw fascism coming and it could just drag the whole world into an apocalypse and none of us is prepared to deal with that and that there is nothing coming. That the whole dream of a proletarian revolution was completely betrayed and maybe, was inherently totalitarian and that the gutter of it was a Soviet Union in that what we’re left with are totalitarianisms, none of which can rescue us. And so there’s something about Adorno that I really admire, is that he’s a very hard-bitten, white knuckle person who’s horribly experienced what it is like to be exiled by fascism and thrown into America, a country he hates for its pop culture, its complete subservience to consumerism and capitalism and yet at the same time he isn’t willing to embrace any form of hope. He has no expectation that hope is coming, that we’re one revolution away, we’re just one strike action away, we’re just one… And so in that way people often find him extraordinarily pessimistic to read. But I like to read Adorno because he’s on the one hand incredibly hardcore in his diagnostics but at the same time there’s not a lick of optimism, that he can’t hammer down very, like with like a rigorous analysis. So I appreciate the fact that he’s critical but without any hope of redemption and I appreciate, I’ve always loved that fact about him. It’s like Christianity but just Good Friday. Christianity with no guarantee of the Sunday to come or Judaism, that’s just the years of bondage but no hope of Moses. And I’ve always appreciated that., his again white knuckle embrace of the way things are and so I appreciate, or the way he sees them at least in his very critical line.

So, yeah, if you’re looking for Hope in Adorno, or anywhere in critical theory, go elsewhere. Go hang out with the orthodox Marxists they’ll sell you hope.

AP: Are you an orthodox Marxist?

JS: No, I’m probably much more on the camp of Adorno. Like I’m very heterodox when it comes to the way that I approach historical materialism. I also think that Marx basically discovered the fundamental laws that govern society but his historical materialism is correct, the critique of capitalism is true but the solution, I think, is Marx’s solution is hopeless.

AP: Violent.

JS: Oh, I don’t care about the violence, the violence is fine that’s just …

AP: (laughing) Okay.

JS: I mean Hegel called history a Schlachtbank, a slaughter bench. I’m totally fine with the possibility that it will almost certainty that it will involve violence. I don’t think you’re going to get out. I don’t think there’s any outside. So in that way, I’m much more on board with a sort of Frankfurt School thing. I also should guess I should out myself here, that on my dissertation committee was Somogy Varga whose teacher was Habermas whose teacher was Adorno and Horkheimer. So I’m…

AP: Somewhat part of the lineage.

JS: I’m somehow part of the problem, that I’m like…

AP: And so since you are critical of Occultism. I think one of the things that I want to ask you is, what is about the things against Occultism? Because before we started doing this you said that you agreed with him and I said very clearly that I did not. So I’m curious to know in what ways you agree with Adorno. And then I have another question but…

JS: I think the way that I agree with him is just in the sort of very boilerplate, boring way that I think of… That I’m a materialist. I just don’t see evidence that there are occult forces outside of The Standard Model. There may be but there are not the occult forces described by Agrippa or De la Porta or Aleister Crowley, they’re occult forces that are things like dark matter or something. And so in that way, in a very boring way, I agree with him that Occultism is a regression in thought. But in the same way that I think that if you don’t agree with the standard model, I think that was a regression and thought or that, if you believed in a god, it would seem like a regression in consciousness. So for me the regression just is not about Occultism particularly it’s about more or less agreeing with Marx’s critique of religion to be found in the introduction of the philosophy.

AP: And what about the people that do experience the occult forces? And for them, it is actually part of their experience?

JS: Oh, I can’t judge experiences, I’m not a phenomenologist. In fact, I’m an anti-phenomenologist, and a structuralist, so I just don’t count experience as evidence. So I’m not…

AP: What do you count as evidence?

JS: I mean basically I mean experience in this experience in the sense of what’s quantifiable, again I’m a pretty militant structuralist and so what’s not quantifiable…

AP: And do you not think that it’s…. what’s the term. Reductionism …

JS: I’m a hyper-reductionist.

AP: … a form of reductionism collapsing the possible aspects of reality into just one that feels more comfortable.

JS: Or one that provides us with a parsimonious story of how the what makes sense of the most data, but yeah I’m a reductionist. I’ve never understood why reductionism is a dirty word. Reductionism is the single most successful theory in the history of theories.

AP: Well, I obviously disagree but …

(laughter)

JS: I mean in a sense of in the sense that it is reductionism predicts with the highest degree of certainty what we observe and it predicts what we don’t observe and why we don’t observe it and what are the conditions under which it will be observable.

AP: Yes, reductionism is useful. This is what you’re saying usefulness and truthfulness are not the same things.

JS: I think it’s more, I think it’s not just useful but it’s also the case that insofar as we have any access to reality at all, it describes not just what we have access to but also what we don’t access have access to and why. And even what’s the most important is just the aspects of reality that are completely anti-human and so they are totally, they defy our phenomenology, things like at the quantum level and things like that. And so in that way, I would say that it’s precisely because of the inhumanity of what it describes that it has nothing to do with us in our perceptions that I am much more likely to believe it. When reality bends to how we perceive it that is when I’m the least willing to accept experience because there are no selection pressures on us to understand reality, just none. And so it’s in that way that of all the things that I count at the very little is subjectivity. I think subjectivity, I mean I’m frankly an eliminativist when it comes to subjectivity and in that way, I am even more radically not on board, at some level, with Adorno because Adorno still flirts with phenomenology in a way that I find just uninteresting and uncompelling.

AP: Well, I’m definitely more of a phenomenologist than you are.

JS: But I think most people are more phenomenologist than I am. I’m hanging out with the Churchlands, for folks who know the Churchlands, who are ellimitivists about consciousness. I’m not even a substantivist about it’s not even whether qualia exists for me, I’m anti-qualia and anti-consciousness. Like I’m on team Paul and Patricia Churchland even when it comes to consciousness as an ontological category. So in that way, I would even be further away than someone like yeah then even someone like Lacan who I’m more sympathetic to because he removes as far as possible the subjective in the human but even he doesn’t go far enough I think but I’m more comfortable with him. More comfortable with look with structuralism a la Lacan than I am with even critical theory a la Adorno.

AP: I think the reason why a lot of people consider reductionism a dirty world is because it feels limiting, it’s like you have this reality in front of you that is well, for those who are perhaps more phenomenologists, that’s multifaceted and has so many different angles and perspectives that you can look through and you just decide to only consider the elements and the aspects that are quantifiable, measurable and universalisable and standardisable. So it feels like a massive limitation towards your perception of reality, your understanding of reality your experience of reality. But of course, maybe, in your case that’s not, particularly a concern. So I think that that’s why, for a lot of people, it is, as you said a dirty word. And I would agree with that in terms of … I’m not a structuralist like, you know as you are I’m more of a relativist. I’m probably a radical relativist. Sometimes, as you know, I define myself as an active nihilist, even though that is sometimes considered a dirty word and something pessimistic which is not really my case. When I say nihilist it means that nihilism comes from the Latin nihil which means nothing. So it means that nothing exists in and of itself in a Buddhist way, in a Buddhist conception of the term nothingness. So it’s not that nothing exists but that nothing exists in and of itself, in a separate manner and all things exist in an interconnected way. So obviously, since I have that kind of perspective I’m also relativist which means that I think that you can have different truths about reality and different ways of seeing reality and they can be both viable because you may be looking at them from a different perspective. You know, if you look at the Earth from the Moon and if you look at the Earth from the Earth you will have a different image but maybe you will see that’s why I don’t rely on perception. But I think that not relying on perception and phenomenon is just deliberately ignoring a big part of the picture.

JS: Or it could be the case. I mean guess I would just say that I don’t think that truth only applies to propositions, not to experiences.

AP: Well yeah, I was using truth in a…

JS: or like it doesn’t apply to experiences either. Because experience ipso facto is what you’re experiencing. So that’s why I would reserve truth as a function of logic, not a function of experience. And again what I mean…

AP: In the metaphysical sense.

JS: I mean I’m even a logical realist and so I would even go so far as to say that it that even all true metaphysical statements must also be logical statements and of course, that’s not going to give me any friends here. But yeah, and again to go back to your statement that to maintain a structuralist position is limiting and I would say yeah, definitely, it’s absolutely limiting. But I would appeal to Hegel and say that Hegel famously said that freedom is the recognition of the necessity and that the limitation is precisely what we mean by freedom. And in that way, I would be…

AP: Yeah but Hegel also saw that we can get freedom through a dialectic of opposites. So in that way, that sort of overcomes that sense of limitation because you’re also facing something that is opposed, you know, you have the thesis and antithesis and then the synthesis.

JS: That is as much as Hegel really ever said that I don’t think Hegel …

AP: Yeah, it is the way it is explained to make it simpler.

JS: I don’t think Hegel thought, I mean I think that he says that freedom is that … he even calls freedom without freedom, without the recognition of necessity is just license and license feels like freedom, you phenomenologically experience it as freedom. But in fact, that’s the actual limitation because if you’re just free to do whatever you want, you’re not actually employing your freedom in the interest of a liberation, you’re employing your interest in the interest of doing nothing or something. And so he has a very, very narrow vision. Let’s say, that’s why Hegel loves laws and bureaucracy. He’s like yeah, you can do what you like but you’ll be dead in three days. You have to have laws and regulations and bureaucracy and those things actually make you freer than if you just put yourself on a desert island where you could do whatever you like but you’ll be dead within a couple of hours. The long walk to freedom is actually wed through a necessity for Hegel and has always liked the idea that, yeah, my three-year-old is free but I don’t want to be a three-year-old like that. I’m much freer now than they are and the grown men who want to stay Peter Pan their whole life, they feel free but they’re just sleeping alone by themselves in a room of pizza boxes and like beer and they’re not really free.

AP: Maybe that is their choice, it is their perception of freedom.

JS: It is their perception.

AP: You’re applying your perception of freedom.

JS: No I’m a Hegelian, I’m saying no, they are actually not free, and their perception of freedom does not make them free. I am actually saying no, again I’m here on team Adorno and team Hegel. I am objectively freer than they are. This is why people hate Hegel and Adorno or it’s weird that, and we’ll get back to the text in a minute, this is the weird thing that I find about like people sort of embracing Hegel these days and sort of ‘occulty’ places, I’ve seen some kind of folks liking Hegel and because, maybe, he’s influenced a little bit about by Kabbalah and Jacob Böhme and some occult stuff from the 17th century especially, But Hegel’s not your friend if that’s what you’re coming to him for, because he’s going to tell you like Prussian Protestantism is the apex of history and he will not blink when he tells you that, and obviously I don’t agree with that either but it is absolutely just something about they want the baroque metaphysics of Hegel. but they don’t want anything else. And I think that you can’t have objective spirit without subjective spirit in the Hegelian system. But it’s funny like what people pick and choose from him.

AP: What is it that they picked from Hegel? You know in occult circles.

JS: I think that the thing that I’ve seen people like about him is it is the case that the dialectic is very much informed from the sort of the history of Hermetic spirituality and history of Hermetic philosophy and that his methodology is especially informed by people like Jacob Böhme and Kabbalah and things like that. And so he’s a place where, to some degree, some degree of Hermetic philosophy, a la Renaissance Occultism and stuff like that is making its way into relatively orthodox philosophy. But yeah, people like that but at the end of the day for him, he instrumentalises that in the interest of his own philosophical project. And I think that when you get into his own philosophical project, I think most people would basically get off. And even I think the stuff about the state in the Philosophy of Right isn’t all wrong. I think that the Philosophy of Right is a book that gets much maligned as just sort of Prussian state propaganda. But I really don’t buy that, I really do accept a lot of his arguments in defence of bureaucracy, in the state apparatus. It’s this question of who controls that state apparatus and that’s where you get more interesting stuff from critiques of that kind of stuff from one of your countrymen, Gramsci.

AP: Yeah.

JS: So you want to turn back to the text, maybe get through a thesis or two?

AP: Yeah.

JS: Do you want to start? Or do you want me to start?

AP: No, you can start.

JS: All right, so we’re sort of buried in the middle of the second thesis and what Adorno is talking about here is about consciousness at different levels of historical appropriateness, which again if you’re not a Hegelian you’re not going to appreciate that idea, that consciousness is evolving through time. But certainly, Hegel and Adorno believed that it was, at least to some degree. So he starts;

“As a rationally exploited reaction to rationalise society, however, in the booths and consulting rooms of seers of all gradations, reborn animism denies the alienation of which it is itself proof and product, and concocts surrogates for non-existent experience. The occultist drawsthe ultimate conclusion from the fetish-character of commodities: menacingly objectified labor assails him on all sides from demonically grimacing objects.”

Such great writing.

“What has been forgotten in a world congealed into products, the fact that it has been produced by men, is split off and misremembered as a being-in-itself added to that of the objects and equivalent to them. Because objects have frozen in the cold light of reason, lost their illusory animation, the social quality that now animates them is given an independent existence both natural and supernatural, a thing among things.”

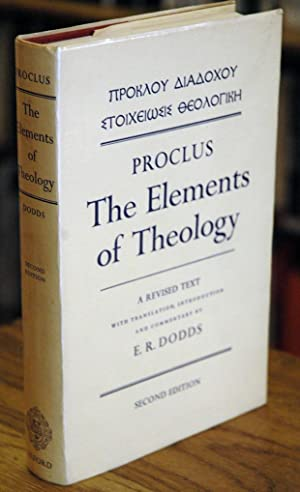

Again Adorno’s famously terse and complicated writing. It reminds me of reading Proclus if folks have ever read the Elements of Theology. Adorno and Proclus read about the same although on obviously very different topics. This is, I think, the point that Adorn’s making here and I think it’s an interesting point, is that one of the narratives that we’ve told ourselves is that the world went through a period of either disenchantment or a kind of a multiplicity of enchantment-disenchantments and the narrative around disenchantment is that basically we went through the enlightenment and everything got disenchanted. That’s been obviously shown to be false, as lots of recent social analysis determines it to be false. What Adorno makes a point about and I think this is interesting and he makes this point in 1947, well before I don’t know disenchantment studies became a thing, is that not only has it been not disenchanted but it’s been re-enchanted but re-enchanted precisely along the only logical lines that enchantment is allowed to occur within late capitalism and that’s through the fetishism of the commodity.

That is the unique purview of which any enchantment, whether it be religion or Occultism or pop occultism or high Occultism or any kind of enchantment is going to happen. It’s going to happen precisely along the only lines that are available and that is the fetishism of the commodity. And therefore I think what he argues for is that when enchantment comes back online or enchantment that was never disenchanted is brought back into capitalism, I think what he argues for is that what stares back at us are not spirits and gods and demons and the kind of things that maybe we experience at some level in the pre-modern world, the pre-capitalist world. But now what stares back at us or actually just commodities? That all of the Gods, all the spirits, all the demons, all the things, they survive but they survive in a different form than the form I would say survivors or commodities. And it is that commodification of the spiritual world that the fortune teller sells to us or the Occultist sells to us or the Preacher or the Rabbi or whatever. They’re all selling to us an experience of something and that experience of selling back to us is a commodity and that it’s sort of, in many ways, a kind of idolatry because the entities that at one level were experienced by our ancestors are gone and the only way they can survive is in the air of the commodity and therefore what stares back at us is just basically a consumer economy of the spiritual.

In that consumer economy of the spiritual, the most important thing about it that separates it from pre-modern spirituality is that, in the pre-modern world, which was a historically appropriate form of consciousness. We experience those things as real we had no reason to believe they weren’t real. Now, these commodities are fake. They’re completely created for us like it’s not just a transactionalism of it, that’s not what he’s worried about there’s always been transactionalism between the gods. It says that now, not only are we not dealing with gods that weren’t there, which, I don’t know, never think the gods were there. Now we’ve created gods that, at some level, we know aren’t there they’re just commodities and now we’re trying to trade with them. And therefore in the spiritual environment, we’re now engaging in basically a religiosity that’s completely created by human beings. And that, created by human beings is us, basically, living in terror as we’ll see of the very commodities that we are responsible for.

So the first thing he was concerned about is that the enlightenment was meant to save us from nature and it created for us doom and gloom via technology and other human beings. We escape that by turning into a spiritual world and there’s no spiritual world that we can ever get into aside from this commodity relationship, the fetish of the commodity and that is I think an obliquely horrible world.

AP: I think that Adorno has constructed this argument from premises that could easily be disproven by somebody that doesn’t really espouse this kind of philosophy. First of all, you have the assumption that gods or spirits don’t exist and so, if you remove that assumption and you try and analyse the argument with a different starting point, from a different worldview, from a different belief system you know the rest of the argument just sounds like a general critique of modern times, not a critique of Occultism. So the critique of Occultism is, in this case, in my view, solely based on his premise and assumption that anything that goes beyond measurability doesn’t exist. And the fact that there are aspects of occult practices or esoteric practices that there are commodities and there are practices that are commodified. But I don’t think that there is something peculiar, specific to Occultism I think that that is part of the contemporary world. And depending on the time when Occultism, occult practices or esoteric practices manifest, of course, they are also a product of the society they are practising in. They are not isolated they are not existing in a vacuum so I think that if you have a different worldview, to me his critique of the modern world and the capitalist society more generally, rather than a critique of Occultism.

JS: Or I think he’s saying that there’s a particular way in which Occultism functions into capitalism. And that’s I think what’s interesting about his position, it’s that if you’re an orthodox Marxist this should have gone away, right? Like it’s a heavily progressivist theory of society such that this should have withered on the vine, Marx says. But Adorno’s saying not only did it not wither on the vine but it’s actually surviving in a new way that it actually lives in capitalism quite well but in a very particular kind of way.

AP: I don’t get it.

JS: Or that or another way of putting it is that Marx generally predicts that in secular societies, advanced societies the religion goes away. So classic secularisation hypothesis, that proved to be generally true.

AP: Institutionally true but not individually true.

JS: And that’s what Marx is saying is that insofar as it does survive it has to survive within late capitalism and therefore it will survive in a very particular way and the question is, how is it that we’re relating to these beings? Beings and broadly construed and what he’s I think he’s arguing for is that insofar as everything has been reduced to the commodity relation, they must necessarily be commodities. And of course, you could reject that and say no, Marx is wrong about that, there are things in the world that aren’t commodities. But I think that insofar as you go along with Marx in that way, that we interact with the world, that necessarily they become commodities. But I think that what’s particularly interesting about this particular case is that of all the things we – it’s ironic – of all the things that we particularly imagine not to be commodities. We imagine things like spirits and gods and demons and metaphysical objects have to be commodities and I think what Adorno is saying is it’s particularly those objects that exist as commodities and only as commodities. They’re like hyper-commodities because there’s not even a thing there to be commodified and yet we can summon these commodities out of nothing.

AP: How does he Define commodity? Just so we are clear on that,

JS: I think that he’s going to say that a commodity is anything mediated by the market exchange. And that’s what separates them from primitive commodities. It’s a difference between going to a ritual practitioner in Greco-Egypt and getting a custom-made amulet. Here, I think what he’s saying is that the social relation is not mediated by my relationship with the ritual expert, it’s the social relationship is mediated through the market and therefore we perceive commodities as having a life of their own. In the same way that like… what’s a good example of this? On the news, when you watch the news they describe the weather the same way they described the rise and fall of the stock market or gold and silver prices. Gold prices fell today and tomorrow it’s going to rain. As if the price of gold rising and the rain coming tomorrow are somehow both naturalised. But we experience a completely artificial thing, the value of gold, and it’s normalised and naturalised in the same way that the weather is naturalised. And I think that that is something that’s very much about how we interact with objects, not as objects any longer, which maybe we did in the pre-modern period, but we interact with them primarily as objects in terms of use value and exchange value, surplus value and that…

AP: Does it mean that Occultists interact with spirits for the value that they get? I’m still struggling to get to what exactly he means.

JS: He means that besides the commercial side of it not he’s I think what he’s saying is that these objects, which went away at some level, have been re-summoned and the only way they can be re-summoned is as commodities. And that they have a life of their own, it’s a completely artificial life but they have a life of their own now. In the same way, other kinds of commodities also have a weird life of their own and there’s a whole episode I want to make about this, about how Marxist theory of the fetishism of the commodity is a kind of magical thing, in a certain kind of way. And the fact he uses the word fetish is a very important term here.

AP: I think that my difficulty is primarily because I’m struggling to see his point because of how much I disagree and so I’m kind of trying to get into the argument but I struggle too because I still think that his critique is just generally a critique of modern times. I don’t understand why would be different the way occult practitioners interact now with Occultism compared to ancient times, to be fair. Unless you premise arbitrarily that gods don’t exist, spirits don’t exist and it’s all just fictional and made up and artificial. I don’t know, I feel like I’m not quite getting it or maybe there is something that I’m missing. Or have I just come from such a completely different point of view that it’s difficult for me to enter into this perspective?

JS: I guess another way of putting it, sort of jumping out to a broader perspective, and this isn’t a unique criticism of Occultism, it’s a criticism of religion under capitalism, is that part of what Marxist critique about religion is not just that religion is all the things that Marxists say about religion. It’s just that it’s also that religion itself must come to obey the market and therefore you don’t even get access to religion anymore. What you get access to is capitalism’s approved version of religion. What Guy Debord called ‘the spectacle of religion’ and that’s, I think, what Adorno is on about here, at some level, is that you’re not even getting access to the gods anymore because they must be mediated to the only social relationships that we have access to and that social relation is the relationship mediated via the economy, in the market. And so you get like I don’t know Kroger Brand Gods, you get Amazon brand Gods, you get the gods of the market allows you to have, you get the spirits the market allows, you get the spirits that are mediated through what you get on Amazon.com or whatever the YouTube algorithm gives you. And so what he’s saying here is there is no relationship to these beings that is not mediated by the algorithm, by the market and therefore…

AP: Yeah, but that is just saying Occultism is like any other aspect of today’s world and is influenced by how contemporary society works but it’s not a critique of Occultism, it’s a critique of modern society because he doesn’t like those commodifying elements of the contemporary society. I think that what I struggle to see is why Occultism is not just any… could pick any cultural product, any other thing, literally, and it would be the same thing, even for philosophy. Then you could write theses against philosophy and say that everything is commodified because we’re living in a society where you do get things off Amazon and there is a certain way of gathering knowledge and acquiring things and even acquiring culture. So it’s not a critique of Occultism it’s a general critique of the contemporary world and then, since Occultism is a product of its time, it will have those elements. but there are also elements that are specific to Occultism that, in my perception, unless I am misunderstanding something or missing something, he’s not critiquing that. Maybe in the regression of consciousness, when he talks about that, that could be more uniquely occultist. Or probably even religion, not just linked to Occultism.

JS: Right, and I think you’ll get in thesis three, right? Now he’s saying, the first thing is the regression of consciousness, that’s the first thesis, the second thesis is there was actually an appropriate relationship to these things in consciousness prior to the market. Now that the market is here, we are now mediated through the market and that provides a spectacular version to use the Borg’s language, and its media through the fetishism economy. But I think this is the reason why he’ll zoom in on thesis three, what his exact criticism is, why it is especially ironic of Occultism and maybe religion more generally, about why this is especially ironic.

So I guess we could get into it in thesis three. But I do think there is something and again this is speaking from his sort of heterodox Marxist position that what he’s concerned about is that when we fetishise a commodity there’s always something false there. When we naturalise it we cover over the falseness. But certain commodities are real like gold. Gold is real right?

AP: It’s a fake commodity.

JS: Occultism, that’s his worry, it’s that at least part of the worry is that with, you know, like a spinning jenny. Marx says, famously, a spinning jenny on the Moon is not a commodity because no one can interact with it and no one can do anything with it. You know gold and you know gold on Mars… is not a good example because we will go to Mars and mine it eventually. But the example of the spinning jenny on the Moon. Commodities are about social relations it’s not about things in themselves. And what Adorno is especially worried about here is that these things aren’t even things themselves, they are things we’ve literally conjured out of nothing and we still interact with them as commodities.

So it’s not just that they’re fake and remember he talks about how the second, what is the phrase, the second mythology is less true than the first one. At least with the old nature-based religion as much as that’s true or it’s not, nature is at least real. You know the famous. What is the comic? It’s like if before we came along you guys were worshipping the Sun and then like the native indigenous people are like, yeah at least the sun’s real and then Adorno is like yes! Right?

AP: Well Pagans do that, still.

JS: Right, and I think that Adorno would say at some level at least that is if you’re worshipping the actual physical thing, the sun, they’re still dealing with an actual commodity, as much as we can commodify the sun. But he’s saying here we’re summoning things out of nothing, rendering them into commodities and then reacting to them and reacting to them as if they’re real. And there’s something doubly regressive about that and that’s the point that he makes in the very first sentence. But why that’s ironic and perhaps dangerous is to be found in, I think, thesis three and again this is all sitting back behind in the background of other pseudosciences that he’s worried about. Mostly like racism and fascism, like he’s already seen people do this, summon things out of nowhere like race, worship it and then lead into all kinds of irrationalism. And I think that’s what he’s worried about, is the way that irrationalism, how we can summon things out of nothing, fetishise them and then act according to that fetish as if it’s real. That terrifies him and I think that’s precisely what is going on here. But I think it’s in thesis three where he says, oh this is the actual effect of it this is how it comes to control our lives. And so I think that’s where we need to turn next to unpack what his actual, what his more specific concern is. It also shows he’s kind of racist too. I like the fact that he’s constantly talking about racism is bad then he kind of gets racist. I always like when people do that.

AP: You do?

JS: Hypocrisy is my favourite thing. I love moral hypocrisy it’s just like the most human thing. I just find that I’m like a connoisseur of hypocrisy.

AP: Well most people are hypocrites, what’s the term? Hypocritical?

JS: Yeah, and most people think they’re not, which is again why I love it so much.

AP: Yeah, it’s just a different extent and I guess it depends on how it affects others.

JS: Do you want to pick up the third or maybe the first paragraph of the third?

AP: Okay.

“By its regression to magic under late capitalism, thought is assimilated to late capitalist forms. The asocial twilight phenomena in the margins of the system, the pathetic attempts to squint through the chinks in its walls, while revealing nothing of what is outside, illuminate all the more clearly the forces of decay within. The bent little fortune tellers, terrorising their clients with crystal balls, are toy models of the great ones who hold the fate of mankind in their hands. Just as hostile and conspiratorial as the obscurantists of psychic research is society itself. The hypnotic power exerted by things occult resembles totalitarian terror: in present-day processes the two are merged. The smiling of auguries is amplified to society’s sardonic laughter at itself, gloating over the direct material exploitation of souls. The horoscope corresponds to the official directives to the nations, and number-mysticism is preparation for administrative statistics and cartel prices. Integration itself proves in the end to be an ideology for disintegration into power groups which exterminate each other. He who integrates is lost.”

That’s the third thesis.

JS: A third of nine, it’s like a Borg name. Yeah, third of nine all right. You wanna take a stab at it?

AP: Well when he talks about the regression to Magic under late capitalism, regression here sounds again like… I guess assuming that magic is in the past something of the past and so instead of progressing through history, you are regressing through history, using a perception of history that goes from worst to better and towards improvement, meaning that what was done in the past is necessarily worse than what is done today, except that magic practices have always existed. “Thought is assimilated to late capitalist forms,” I’m not sure what he means here.

JS: I think it’s just the second paragraph, the second part of the thesis, that thought itself becomes mediated through the commodity relation.

AP: “The asocial twilight phenomena in the margins of the system, the pathetic attempts to squint through the chinks in its walls.” What do you have to say about this first part of the thesis?

JS: I think this is the irony right that he’s thinking about is that it’s really a case of religion generally but Occultism specifically. Let’s take one of the aims, one of the aims of this thing is to somehow know the truth about things, like to know the truth about ultimate reality, either through religion or gnosis or something like that. To know reality, beyond this reality, somehow. A reality that is far more real than that one. If it is the case that thought in late capitalism is always assimilated to late capitalist forms, then the very act of thinking that you’ve thought your way out of it is only further proof that you haven’t. The system itself will sell you gnosis and let you believe that you’ve achieved some breakthrough to a higher reality, all the while laughing all the way to the bank. Another way of putting it is you know Jean Baudrillard, the famous post-modernist and he, when they’re right they’re right, you know inspired the Matrix in fact his book “ Simulacra and Simulation” is actually on Neo’s shelf. And someone asked him, famously, what he thought about the movie “The Matrix” and Baudrillard said the Matrix is the kind of movie The Matrix would make. But it’s a movie that lets you believe you can get on the outside, it’s a movie that lets you believe that there’s an escape from the totality. But it lets you experience it vicariously through a TV character and it’ll sell you the ticket and all the while Warner Brothers is laughing their way to the bank with your gnosis. Which is hilarious by the way because, what is his name now, Andrew Tate?

AP: Oh, yuck.

JS: This is the language he uses, he uses the language of the Matrix. That the Matrix is trying to kill him and take him to jail.

AP: Yeah, I think the alpha males really like that kind of language. Red pill, right?

JS: Yeah, but that’s like the language that gets assimilated and I think that that’s exactly capitalism selling you masculinity right back to you. Like sure we’ll sell you masculine and buy our pills or whatever. I think that Adorno is saying the exact same thing happens in the occult. It promises you a vision of the outside, of the truth, that all it’s doing is selling you a repackaged version of what it wants you to believe and you can buy as many Sigillum Dei Aemeths on Etsy as you like and talk to the Enochian spirits as long as you’re buying them from Amazon or Etsy or whatever.

AP: Well, first of all, I want to acknowledge the fact that there are people in the chat that say that I look bored, I’m not bored, I’m just angry and trying to hold it in. (laughs) So just to clarify that.

JS: This is the funny thing about Adorno he makes people so angry. I’ve never seen a philosopher with the ability to like literally use translated words on the page…

AP: I think the only way you cannot be angry at Adorno is by being as materialistic and a reductionist, I think. It’s because it’s like, to me it’s honestly even a bit difficult to argue against his thesis because they are founded so much in his own idea of the world that it’s like as long as you move slightly on the left or slightly on the right they just fall apart – all these theses. But, for instance, in this case when he talks about – that’s my perception, anyway – when he talks about the fact that… What were you just saying? So remind me for a second. Oh, yeah, the idea that what you get is actually that you get sold something, for instance, to contact the angels and so on. Well, first of all, that’s not even true because it’s not really the case that every time that you need to have an occult experience you need to buy it from somewhere. That is not true. There are many occurrences where people just have their own experiences, even spontaneously and they haven’t bought anything from anywhere. Maybe they were taught by their grandmother or by somebody else they met in their life.

The second; one thing does not exclude the other even if you have to buy a book or buy a course that doesn’t necessarily mean that you’ve been sold a contact with the spirit, it means that you got a contact with the spirit and you have allowed the person who facilitated that to eat and pay the rent. So it’s not really that you get sold something, it is just that you are in a process of exchange where you get knowledge and you allow the person who’s providing that knowledge to survive. So I don’t see that it becomes a commodity when you have a certain mindset and a certain perspective on things. So that’s why, in my perspective, I find it to be a very interesting philosophical exercise but for me, it is really difficult to argue against this thesis, which makes it in a way more of a challenge and more interesting. But it is difficult because it is so alien from my way of seeing things that for me it’s just like well no, it’s wrong, it’s wrong, it’s wrong, it’s wrong.

JS: So right, that’s part of the reason why I wanted to, you know, if I were to invite another version of Adorno on then it would be a very boring conversation. But I think that this is what’s fascinating about it and it’s funny.

AP: And I think … sorry no.

JS: I think what he would say is that the exceptions prove the rule. That in the end, what is going on is for him that these things are being mediated through the market and is mediated through these things and that I don’t know what Magic, what Gnosticism, is more powerful than a single shareholder or OPEC. And he would say…

AP: Well, it depends on the practice that you’ve had.

JS: Yeah, but I’m saying like I think you would look at the global system and say like yeah, you can think that you’re getting access to all this stuff with your holy guardian angel or Enochian spirits or Yahweh or whatever, or the Sephirot and he was like the wrong shareholder blinks and your country plunges into war and I think that’s…

AP: One thing doesn’t exclude the other. I think that’s the problem that I have with materialism and you know with this kind of materialism/structuralism is that it only sees one aspect and it tends to see every other aspect as in a position, as one thing excludes the other. So the fact that you have a shareholder that can have a massive impact doesn’t mean that an Enochian angel cannot have a massive impact as well and in some cases, you cannot measure and it’s not even a competition, that has more power. I think that it depends. From the point of view of somebody who obviously believes in the possibility of having a conversation or a communication with entities, it really depends, it depends on the kind of spirit. There are some that are more linked to the material world and can have more of a hold on it and others that aren’t and tend to provide a different effect on people’s lives doesn’t mean they are less important because they are less linked to the material world and they produce less of an effect on the material world. Of course not, it just depends on what the specific practitioner wants to do.

So one other problem that I see here and probably more generally with materialism, is that it is so nearsighted, that it only sees one thing and if it interprets everything through one small lens and doesn’t see all the other things that are just in front of their eyes, that’s my perception of Adorno. So if you have that kind of narrow view of reality and the only thing you see is the material aspect, then I would say you know you are just setting yourself up for misunderstanding so many things that are in front of you because your lens is so narrow on the world and on reality. That you only accept such a small amount the… I cannot even say the phenomena but a small amount of what is in front of you. What it is that you are analysing. That, for me, it is just so easy to get into a full-on misunderstanding.

JS: That could be true and it could be the case that he’s just very narrow in his understanding. But I think that what he wants to do is say, yeah that narrowness helps Adorno to have a clarity of analysis that would be lacking. The more that we expand into what is possibly engaging in the causal structure, the less we have, the wider or narrow our unit of analysis, and the less we can know what’s actually causally happening and I think what he’s saying is, once we narrow it into this conversation, whether that conversation is true or not, of course, you could reject what he’s arguing, he’s saying when we get ourselves into that position what seems to pop out at us, and I think what he’s saying is popping out to us, is that there is a relationship between this way that he’s characterising the Occult, which may or may not be accurate. He’s saying that the very claim that you can see the outside, like in some kind of mystical way, is for him all the more proof that you cannot because there simply is no outside. He just says no, in a sentence where he says like “while we’re revealing nothing of the outside, illuminate all the more clear of the forces of decay within.” That he uses the example of the bent old fortune tellers terrorizing the clients with crystal balls there’s some anti-Roma stuff here, I think, unfortunately. I think the idea is he’s looking at this and saying if these are true and to what degree if they are true, the question is, if they’re making predictions of any kind about the world, how do those predictions line up with what we can tell about other forces in the world. And if there’s not some kind of parsimonious thing, why trust these people? Like why think any of this is real and even more so, if these things… even if these things are just elements out of the economy.

And I think that another thing that he’s pointing to here, that I think is very interesting, is that he’s pointing to a dual irrationality. That there is an irrationality, for his part, on the point of the Occult which basically summons things that aren’t real and acts according as if they are. But he’s saying that exact same thing happens in capitalism, that we summon something that isn’t really in the market and then bases our entire life around it as if it were real and I think that’s why he’s jumping back and forth between horoscopes, a number of mysticism and like administrative statistics and cartel prices and like the fortune tellers and other kinds of people working in these kinds of think tanks and stuff like that. He’s saying both of these represent a kind of unfreedom. And an unfreedom that we have conjured into reality, that we subject ourselves to that isn’t real and we’d be better to dispense with both of them, both mystical fetishisms coming out of the commodity relation. But also the market relation that dominates our lives, it also is equally unreal and yet these things are more similar than the two would think.

AP: And what about meaning, I mean the fact that there are people that engage in these practices and find meaning in them? Obviously, something that he doesn’t take into account because meaning is not something material, it’s just something that can allow people to keep going and wake up in the morning instead of just vegetating. But it’s not material enough.

JS: Yeah, well I think you would say that. I mean we all eke out meaning, the best we can give the world that we live in. I’m sure the medieval peasants eeked out meaning in the way that they could. But it’s an unfree meaning and therefore is the less free meaning and so I think he’s less interested…

AP: By freedom? By freedom, he means freedom in Italian terms or… So freedom in Italian terms is more the actualisation of spirit in history. And so how would that translate into individual engagement with the Occult?

JS: I mean with Hegel or with Adorno?

AP: With Adorno’s perception.

JS: Adorno thinks it’s like a shell game, that it’s a regression in thought. It’s inherently less freeing because you start off free then you conjure a bunch of commodities to control your life and then you follow their dictates, as opposed to not listening to spirits that he thinks aren’t really there.

AP: Yeah, that also assumes that Magic doesn’t work because otherwise, you would think that if the Occult is effective like many occult practitioners think, then they would say that it makes you freer, rather than less free because it extends your agency in the world.

JS: Yeah, and I think that I mean to follow Adorno’s thinking he would also say the rich will tell you that they’re freer because they have more money and can do more stuff. And if a rich stock broker or a banker is going to say, yeah, more free than you working class YouTubers. I have all this money. I can do what I like. And I think Hegel’s going to say, you’re not actually and Adorno’s going to say, you’re actually not free, you’re a slave to a market that enables you to a certain lifestyle but freedom is not that. And ditto the perception of attaining knowledge of the outside is not the same as actually attaining knowledge of the outside. The belief is distinct from knowledge and again Hegel and Adorno both are kind of elitists when it comes to this, they’re objectivists and they’re just going to say because you think you’re free doesn’t make you free.

AP: And what makes you free?

JS: I think that Adorno has a very particular idea of freedom but I think that in Adorno’s uptake of freedom, it’s to be in this sort of Spinoza, right, that freedom is the ability to be compelled by the least amount of outside forces and I mean compelled, not that outside forces can’t and instruct you but to be compelled means that you’re inherently unfree. And insofar as Adorno’s right and one can argue if he is or isn’t if it is the case that in late capitalism our interaction with the world is mediated through a fundamentally immoral and maybe even irrational, probably both, if it is mediated fundamentally through an irrational, immoral market then we are compelled by that and therefore unfree. Ergo I think Adorno is going to say, that we have to basically dismantle an artificial system that is there to make us unfree in the interest of exploiting surplus labour value from us.

AP: I can understand that point although I would argue that the idea of freedom as being compelled by the least amount of external forces is a utopia because you are always subjected and conditioned to outside forces. You need food, you need air, you need sunlight you may need supplements if you live in the UK and don’t have sunlight. There are many things that you are, in a way, subjected to and that condition your existence but that is also because I come from a point of view of perceiving everything as extremely interconnected and so obviously not all Occultists have the same exact worldview, but many do endorse that idea of interconnectedness. So for them, it wouldn’t be a renunciation of their freedom because they don’t endorse it in the first place, the idea that freedom is not being compelled by the least amount of external influences. The idea is that we are continuously and inevitably immersed in the web of life and into a web of interconnected things. And seeing it as otherwise is a narrow view of what is actually there because if you are only considering certain things and you exclude many others then you can say, okay there is a possibility of being influenced by the least amount of external things but you are cherry picking what are the external things to the point where you make that concept possible, to begin with. Whereas if you were to acknowledge all the things that influence our very existence, let alone our thoughts and our being in the world, then it would just become a utopia to think that you can achieve freedom according to that definition.

JS: I mean to be clear Adorno doesn’t think that we can escape like natural… it’s not for him, external compulsions that are natural I suppose, although they have a particular peculiar view of nature in the Frankfurt School. It’s unnatural compulsions that we don’t even recognize we’re being compelled by. That Marx famous has said “they do it, yet they know not that they do it” – those are the compulsions that he’s worried about.

AP: So the unnatural ones?

JS: The unnatural ones we think are natural. It’s the fact…

AP: The unnatural that we think we’re a natural, okay.

JS: And we need friends and sunlight and food – it’s not like that. And Adorno and they are not transhumanists or anything like that, of course, but they’re more worried about interactions with commodified things that we take to be real that aren’t. That’s what he’s worried about. It’s not that they reject the idea that we’re all interconnected or interconnected or interdependent in fact they accept the very Hegelian idea that freedom actually just is interdependence, the recognition of interdependence. But it’s that the things that we’re dependent upon that we shouldn’t be dependent upon, that we’re told that if we’re not dependent upon them we’ll die. Like the market, like commodities, like wage labour, like those things are not natural. Now they may not be inherently bad but they’re not natural and we do not have to live in a world that’s mediated by the commodity exchange because that world hasn’t always existed and there’s no reason to believe that it will. That we could easily imagine a world beyond commodity exchange being the fundamental unit of social selection.

AP: Yeah, but perhaps the fact that it has developed in a certain way, it is because it was also useful at a given time in history. But my perception is that he tends to split his understanding of things into very minute categories and creates his own labels and then within that very narrow space, he argues against things that, you know, whose argument can only really stand within that very narrow view of the things because for instance even the idea of what is natural and what is unnatural – it is a dualism and a dichotomy that, is it really like that? I mean it takes … enlightenment, really takes

JS: In the Frankfurt School, the idea of the natural and unnatural.

AP: Yeah, in the Frankfurt School, yes, but in a different kind of view you may have the perception that actually everything that exists in the world and that you can interact with, is natural because it is part of nature. So if something is unnatural by definition could not even be, could not be brought into existence in any possible way. You know, not in thoughts not in actions, not in productions, not in anything. So everything that sees the light of the mind or the day or the actions or the production, is natural by definition because it is part of nature.

JS: It’s funny that you mention this because he’s gonna take exactly that distinction to task in the next thesis, where he says that one of the interesting things about Occultism and one of the interesting things about critical theory is that they both reject the rationality of the real. Like Hegel famously said that the real is rational the rational is real. And in Marxism, in Occultism and Adorno all have a problem with that, that at some level they’re gonna say, yeah, sure … Hegel was right up to a certain point but not anymore and that Occultism will respond to the failure of the reality of the rational, Marxism will respond to the failure of the reality of the rational and Adorno, I think, will be the one person who actually holds on to it. And so in this way, Adorno will out Hegel both Marx and Occultism. So it’s interesting that you come back to the idea of this is their critique of nature, they’re going to say, no actually what is unnatural is anything other than this, this is natural actually. It just happens to be horrible and we have to deal with it that way as opposed to banging your head against the rational and saying be otherwise, be a spiritual world, be a proletarian revolution, be anything other than this, like this world, just be anything other and Adorno is going to say nope, no utopia is coming and there is no outside. And so in this way, this is where…

AP: It’s just about how fun Adorno is.

(laughter)

JS: Of course, he’s so unfun!

AP: And then you wonder why people hate him. I mean…

JS: I just again, I find for me it’s just always interesting, like what, I don’t know, cranks people’s tractor and these kinds of things. Like what makes people so… No one’s gonna get emotionally animated about, I don’t know, Sellars, yeah no one out there is being like, okay I’m gonna flip out, I’m gonna like punch the wall because of Sellars or something. I don’t know there’s no one I’m trying to think of someone who just doesn’t make any feel any one way or the other Quine or something, I don’t know.

AP: But Quine is a logician.

JS: Correct. He did more than just logic. There’s something about…. and this is the reason why I love to read Adorno and why I like studying him, and this is really him, not the Frankfurt School. Because reading Benjamin is much more like reading philosophical poetry and reading Horkheimer’s is just like reading straight-up cultural theory. What I like about reading Adorno is he just doesn’t stop, he doesn’t let you breathe, he doesn’t let you rest, he doesn’t give you a moment to, what’s the right word, he doesn’t give you a chance to take a rest.

AP: And to be happy.

JS: Oh he doesn’t care

[Laughter]

AP: That’s definitely off the table.

JS: No, which is funny apparently because he was not, in life, a very sour person they say that – what was his wife’s name?

AP: Oh, poor wife. Has she run away with his best friend? I hope so.

JS: YouTube throwing the shade on Adornos. He may have been a freak in the bed for all you know. He has to let some of this energy out somewhere. Oh, she had this very German name. What was her name? It was like Ingrid or something like that. What was her name? She had like the most German name ever. I’m surprised the Nazis kicked him out with a wife with a German name like that. Like Hilfrida or something. But people often asked her like, was he like a sour puss in real life? She’s like no, he’s a fun guy to be around. In the same way that people think Kant was a completely boring guy but apparently he was the most fun to be at dinner parties and stuff with. Yeah, I like Adorno I think that philosophy when it does its job very well challenges us to take fundamental assumptions that we have about the world and it challenges us to them.

Oh, Gretel, Gretel. Oscar Diaz has it, thank you. Yeah, her name’s Gretel which was just like one of the great German names. But I think part of what I like about him is that even if you’re a complete idealist or a nihilist maybe, he’s very challenging because he is very much anchored in this world and in the very commodity structure of this world. And if you’re a Marxist, he’s also very challenging because he says not only is your Marxism not gonna work but you’re not even trying hard enough. You have to think deeper about these issues, like your mechanical materialism is not going to explain society, actually, sorry. And your hopes of some glorious revolution are not going to escape the problems of totalitarianism. In that way, I think he’s a very challenging character because he never lets anyone rest. The Marxists don’t get to rest on their laurels. The postmodernists sure as hell don’t. Don’t even get started on letting some Derrida, postmodernist, deconstructivist types in this room. But also he’s not going to let anyone rest. And in that way, I think he’s a real philosopher he’s a gadfly. People hated Socrates for this reason.

AP: Yeah, I mean I respect him as a philosopher, it’s just that I fully disagree with him. So it’s not a lack of respect, of course.

JS: Yeah,I mean I know also I disagree with a lot of the things that he comes to. But I think this is an interesting place where he’s taking some of the ideas, that I think a lot of people that watch our channels take for granted and a lot of people who also are sort of left-wing people, on our channels, also take for granted, saying yeah, these two things don’t play together actually. Not easily at least. Not without some philosophical work and I think that that kind of critique is incredibly insightful. And even if you disagree with them getting at how he thinks is I think a very powerful and

interesting philosophical exercise.

AP: I agree.

JS: All right we got through two.

AP: Yeah, so it was more yeah we got through more theses than last time, which was just one.

JS: Yeah, so we’re up to number four now, which is when he gets more into the effects of it I suppose. The effects of how Occultism operates in this.

AP: Yeah, we can do that next time.

JS: Yeah let’s do that next time. All right folks, thank you guys for coming along with the analysis of this difficult and challenging text. Both difficult and challenging – just understanding what the hell he’s talking about because he’s a pain in the ass writer. But also coming along to be challenged by his ideas that, you know, that’s what philosophy does. Reading people who agree with you isn’t philosophy, that’s called an echo chamber.

AP: And social media does that so well.

JS: Yeah and that’s part of the reason why I chose this text is because I knew this would be a text and I’m curious to look to see how many subscribers I lose as we work through this.

AP: I don’t think so. I would hope not.

JS: I’m going to check it just to see how many drop out just because of this text. But you know if you want to complain about the algorithm and be like, oh I hate being served things that I already agree with. Well, welcome to Esoterica where literally we talk about Magic in one episode and literally take it apart in an extended series. So this is my…

AP: I defend it though.

JS: Yeah, you can. just it’s the dialectic but that’s what matters to me is actually hanging on to the dialectic even when the algo-gods, deeply mediated by capitalism, are trying to tell us how and what to believe and the more we can resist that, I think we can all agree, we’re all better off than

where we can resist the way that the algorithm wishes to manipulate us.

AP: So are the algo-gods real gods?

JS: I would say they’re more real than Enochian spirits are. I’m more terrified of the algo-gods and that I am, I don’t know.

AP: That’s because they affect your life more directly.

JS: The planetary Spirit actually. I don’t know, planetary spirits might be doing all kinds… well my power keeps getting knocked out. Who knows, I ought to go consult an expert on that stuff. I’m not an expert there.

But all right folks we’ll pick up with this more and maybe next week or the week after. More Zohar on Thursday. Oh wow, Friday I just got finished rough editing a 50-minute episode, finally, on Yahweh. You guys have been asking for an episode on Yahweh. So I just did a 50-minute-long episode on Yahweh. I just recorded this morning and this Sunday is absinthe thing. So I’ll be doing some absinthe content on Sunday with my absinthe colleague Adrienne LaVey, who is really an expert.

AP: Yeah, she’s also a follower of my channel and I used to follow her from before I had the YouTube channel actually. for different reasons. because she’s a goth content creator. I think that she moved more towards making content on absinthe in recent years.

JS: Yeah and also you guys are both singers. She’s like releasing her absinthe single on Sunday too. So we can check it out but anyways Angela what have you got going on this week? Would you mind sharing, please?

AP: Yeah, I have a very interesting interview with a professor from the University of Vienna on Sunday at 6:30 and it’s gonna be on Global Tantra and Buddhism and Taoism and Professor Julian Strube, speaking of German people, he’s German and he’s working on a new methodology for studying these subjects from a global perspective. Because at the moment we tend to think more about Western Esotericism and now there are scholars that are arguing more that we should expand our field more towards a global perspective on Esotericism and not just tackle Western Esotericism, even though Western Esotericism, I think, makes sense as a category because it is something that is definite and had its own traits. But yeah I have the interview coming and then I have content coming every week on the academic study of Esotericism, Magick, Paganism, and Shamanism so make sure to check out Angela’s Symposium on YouTube and all the other social media because I’m kind of everywhere. Adorno would hate me for that but he probably would hate me for many other reasons as well.

JS: That’s actually precisely why I’m not on all the social media is because of my post-traumatic Frankfurt School trauma of like of mass media or whatever. That’s at least part of the reason why I don’t have any other social media. I read enough of this stuff to scare the living bejesus out of me. But I’m probably rational for that.

AP: You’re very materialistic.

JS: I don’t know. I’m not materialistic in the sense of well, that’s not true I also like nice things. I’m both – who doesn’t want some bling that’s the best?

All right folks well thank you for joining us for this conversation and make sure to check out Angela’s content, and consider supporting her work on Patreon. She’s a fantastic content creator and a dear friend and a respected colleague. So make sure to support her and yeah, see you guys in a couple of days for the complete opposite of Adorno the Zohar. So see you folks in a couple of days. Y’all have a great day, thank you.

AP: Bye everybody.

First streamed 1 Mar 2023