Dr Justin Sledge JS: All right everybody, welcome back to another one of these sorts of experimental Esoterica things where I bother my friends and colleagues and scholars to come and read turgid, complicated, maybe deeply misguided texts in Western Esotericism in general and to see if they’re of any interest. And I’m really happy to be joined by my fellow colleague and also a fellow philosopher. Folks know, probably know Dr Angela Puca from Angela’s Symposium focusing primarily on contemporary stuff in Paganism and Shamanism and Magick, Magick-practising cultures but I think most folks, many folks don’t know that Angela also has a background in Philosophy. We’re the mirror image of each other. Where I got the PhD in Philosophy and the MA and Religious Studies, Dr Puca has the opposite and so in that way, we’re a good fit to talk about the intersection of Philosophy and Esotericism as much as it is. But Dr Puca thank you for joining me.

Dr Angela Puca AP: Thank you for inviting me over. It’s gonna be interesting because you and I have, surprise, surprise, opposing views.

JS: So yep, we have different views and also we’re trying something a little technical and…

AP: It’s not working. I just saw that it is not working. So I put a message in the chat that if it wasn’t working that people should now head over here.

JS: All right we’ll have to try it a different way next time. I don’t know, we’re trying to have it stream both at the same time. Both on my channel, and Angela’s Channel and it looks like the technique we tried didn’t work. So we have to try another one next time. Sorry Angela

AP: It’s fine.

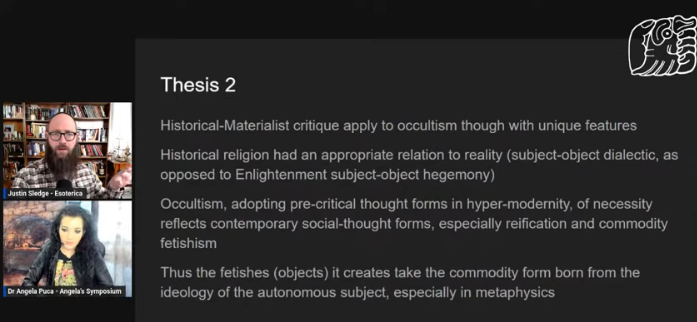

JS: This is technology stuff. So the text we’re talking about today and maybe more than today because it’s a difficult, turgid text is Adorno’s, Theodor Adorno’s 1947 text “Theses against Occultism” and there’s a lot we could say to introduce the text. I guess I’ll just say a couple of things the historical situation in this text is really interesting. It’s written in 1947 this is the last couple of years of Adorno’s time in exile because of fascism this text is found originally in “Minima Moralia” and at the very end of Minima Moralia and it was published around the same time as their really famous book “The Dialectic of Enlightenment” which really ushered in the age of Critical Theory now, for whatever reason, critical theory has a really polarizing effect on people, and Adorno especially has a very polarising effect on people. I don’t know why that is exactly. It’d be interesting to study the psychology of why certain thinkers polarise people in the same way that they do. But at any rate, this text is just hard. Adorno is a notoriously difficult thinker and this text is tough and it assumes a lot of background knowledge, especially around Hegel and his particularly weird version of Marxism.

And so to get into it we’re going to be sort of unpacking it as much as we’re explaining it and certainly as much as we’re agreeing or disagreeing with it but I guess that’s all I have to say about the text in general, I don’t want to go into a whole spiel about critical theory and what that is and what that isn’t. I think in some ways this text stands on its own and when it does intersect with a larger project of Adorno and Horkheimer’s intellectual concerns especially as they’re found in Dialectic of Enlightenment. I guess we can make that clear but aside from that Angela, any sort of introductory words about the text or any introductory comments before we get into it?

AP: That I will get angry.

(laughter)

JS: That’s fantastic.

AP: I think that the Adorno and the Frankfurt School are very interesting, especially from a methodological point of view. And as you mentioned for the critical theory and also for their interpretation of Marxism and the understanding that they had of pop culture and how that becomes consumption of a certain kind. So I think that Adorno and the other members of the Frankfurt School are very, very interesting. So I will try not to be too polarised when we have this good discussion because we can start by premising that Justin is more in line with Adorno’s view and I’m very much in disagreement with it.

JS: I think the way that I agree with him and the way I disagree with him or I think will become clear but I don’t totally agree with him. I think he’s doing the exact same thing he accuses so-called Occultists of doing and I guess that’s where we could probably open it up and I really want to point that out, I think that Adorno is doing the same thing that the people he’s accusing of doing that thing are doing. So, insofar as I agree with this text, it’s an indictment of Adorno, I think he’s right despite himself. Not because he’s some genius, it’s ‘demolish Occultism’ or something like that. And I guess that’s where we should start, Angela and I think this is where your beef is really going to begin. Is the title right? “Theses Against Occultism.”

AP: Yeah one of the things…

JS: Sorry. Please this is where I think you have a really really important critique of Adorno just right out of the gate.

Yeah, because we were discussing this right before the live stream. I was criticizing the very fact that he is offering us theses against Occultism or the Occult but he does not define what the Occult is. And in fact, as we will see, he tends to lump together things that, within those who would have considered themselves Occultists at the time, they would have distanced themselves from those kinds of practices and so I think that the first problem that I see with this text is the fact that he advances thesis against the Occult but we don’t know exactly what he means by the Occult. We get some examples and by the examples that he gives, he gives the impression that under the label Occult he’s lumping together all the things that he considers to be quote, unquote irrational. So my first critique is that he doesn’t define what the Occult is and that he is the way the definition emerges from the text is in total disregard of what the actual community of practitioners of the time, those that were practising the Occult, would have defined as occult and what would have been included and excluded. So, usually, one of the things that you do when you do research, maybe not as a philosopher, but when you do research as an academic you end to have a rationale for the inclusion of data and for the exclusion of data. In this case, we don’t really have a clear sense of what is included and why within the definition the Occult or Occultism and what is excluded and why. So we don’t really have a rationale for the inclusion of elements and exclusion of elements. So to me, that’s the first fallacy that I see.

JS: And I think that’s a very, very important point to keep in mind. I guess I would say just a couple of things about that and I think I agree with you that a real weakness of this document is that one of the bugs or features of this document is just a series of theses. We’re not getting axioms and definitions. This is not a Spinozistic text. Theses, from a philosophical point of view, are texts in need of proof. So he doesn’t supply the proof, he just says these are things I think are true they might or might not be true but to what degree they are true we would have to fill in the gaps. And I would proffer that basically, you’re going to agree or disagree with this text to the degree to which you’re basically a Hegelian. And if you’re not a Hegelian you can just throw this text out the window and you can go play…

AP: I would imagine that most aesthetic practitioners would not be Hegelian.

JS: And that’s the point I would want to follow up on is that I think that Hegel has had this interesting resurgence, in Occulture recently, precisely because they see him as one of the few philosophers carrying the banner of Hermetic Philosophy and Kabbalah into his Philosophy through the dialectical method and that’ll be a curious place to see to what degree Hegel is on team Esotericism or team not. I think from obviously Adorno’s position he isn’t. I

AP: I think maybe also talking about Hegelian can be a bit too generic because when I said I think the most esoteric practitioners are not Hegalian I mean in terms of the view of history not necessarily the implementation of the dialectic but more the idea that history moves from worse to better, that there is you know the perception of progress, that things get better over time.

JS: Right and Adorno and Horkheimer have a very strange conception of progress. They believe in it but they’re very critical of what is constitutive of progress. Of which reason is not necessarily progress for them. Then again, I think that’s maybe where I would jut up against you a little bit, Angela, where I think that he’s not taking just the irrational because he’s not totally against the irrational, I think that what he’s worried about is a certain kind of irrational that’s outlived its position in history, that the rational or irrational are historically situated ideas and that he’s worried about a certain temporal displacement of the irrational. And I think that’s his concern it’s about where the irrational is in history and why it is there. But I wonder also if we could just use sort of a Hanegraaffian model of Western Esotericism to…

AP: Rejected knowledge.

JS: Yeah, rejected knowledge. This is all the stuff that is the rejected knowledge thesis and I think that it may be a bad fit but it wouldn’t be a totally wrong fit here.

AP: Not totally inaccurate. Yeah, it’s close to what he probably would have defined as occult.

JS: So I think that maybe a handle for folks – if the word Occultism is just offsetting because it’s too broad and I really wonder how the word Okkultismus functioned in German in the mid ‘40s because this term functions in lots of different ways, in lots of different times. So I wonder how it functioned there in the ‘40s in German but I think that we can get a bit of a handle on it from a Hanegraaffian point of view. But there’s no easy way to do it I think we must have to go in.

AP: Ready?

JS: Yeah, let’s do it. Also, I’ll just say that Adorno is an unabashed elitist and so if he comes across as an elitist to you, you’re right. He just spews invective whenever he wants and he is an unabashed elitist and so this is a case where you can see it just full well. Now him being elitist doesn’t make him wrong, it just might make him really grating and irritating. He’s one of those guys on Reddit.

AP: Yeah, he’s a bit irritating in my opinion, but …

(laughter)

JS: Okay, so we’re just going to read through it and take some natural breaks and unpack it as we go so I guess I’ll start since I’m the since I invited Actually you on this ride. I’ll take the first text, the first blow here.

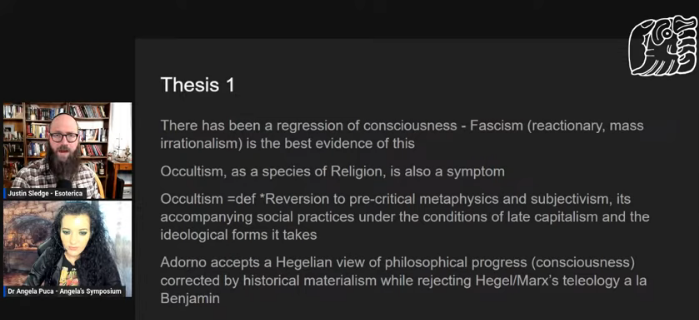

So Thesis One:

“The tendency to occultism is a symptom of the regression in consciousness. This has lost the power to think the unconditional and to endure the conditional. Instead of defining both, in their unity and difference, by conceptual labour, it mixes them indiscriminately. The unconditional becomes fact, the conditional an immediate essence. Monotheism is decomposing into a second mythology. Quote, ‘I believe in astrology, because I do not believe in God,’ one participant in an American socio-psychological investigation answered. The judicious reason, that had elevated itself to the notion of one God, seems ensnared in his fall.”

I do particularly like that image that reason and God are both snared to each other and are in a fall.

“Spirit is dissociated into spirits and thereby forfeits the power to recognise that they do not exist. The veiled tendency of society towards disaster lulls its victims in a false revelation, with a hallucinated phenomenon. In vain they hope in its fragmented blatancy to look their total doom in the eye and withstand it. Panic breaks once again, after millennia of enlightenment, over humanity whose control of Nature as control of men far exceeds in horror anything men ever had to fear from Nature.”

All right, so there’s a lot going on here, obviously and if you read it in the original German it is separated line by line. I think that’s a much better way of separating it because often these texts are not totally connected here. But I guess the few things I will say is that the first line, in terms of regression and consciousness that’s straight Hegel. Hegel is assuming a progression in consciousness. Now what makes Adorno interesting here is that Hegel never accounts for the possibility of a regression in consciousness. For Hegel, consciousness is always in a progression. The idea that there could be a regression here already signals to us that there is a very strange relationship to Hegelianism here. How is it that a regression could happen? Well, the only way that a regression could happen in a Hegelian dialectic is if the dialectic moves backwards. And what’s important about that is that Hegel thought that it couldn’t move backwards or it didn’t because of the movement of absolute spirit. But because Adorno is a weird Marxist he thinks that it could move backwards based on the material conditions of reality. And that’s exactly what he thinks has happened. Is that we’ve moved forward on one element of the social register i.e. rationality and technology and the control over Nature and things like that but that rationality has actually moved forward in a way that has actually not been totally successful.

So we’re two steps forward one step back and that’s the negative dialectic that Adorno is famous for, the idea that we take two steps forward one step back not two steps forward and then sublate and move up the way the Hegel thought. So if there is a regression in consciousness, which is a totally strange but still a Hegelian idea, the question is what is that constitutive of? What does that look like? And he thinks that it’s the loss of the ability to think, the unconditional right and to endure the conditional, that we’ve lost the ability to think the absolute right or endure the conditional – which is the world around us the world of what Hegel will call subjective – a subjective spirit. And what the symptom of this is it seems for Adorno is that the unconditional becomes fact which, for Hegel, it can never become fact. The unconditional is the absolute, it was never a fact you only reach it through the conceptual process of logic grinding toward the absolute and that the conditional becomes an essence. That could never happen either on a Hegelian model because the conditional was always conditional, it’s always conditional upon something and therefore never has an essence. But that’s what he thinks, what he’s defining, I think, as the Occult is at some level the absolute, has been surrendered, is no longer thinkable and that the unconditional becomes fact and I think that’s what the first part of what he’s getting at. That is to say that consciousness has gone off the rails but the reason why consciousness has gone off the rails has to do with society and not to do with some abstract movement of the dialectic. Angela, any thoughts about the first part up here?

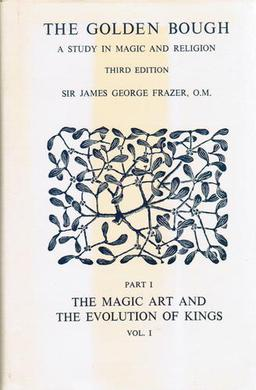

AP: Yeah, another thing that Adorno reminds me of here is also a certain view of Occultism or Magick that comes from certain armchair Anthropologists of the 19th century that have studied Magic and were particularly popular, such as James Frazer and Tylor and in particular with Frazer and the Golden Bough we see the idea that history progresses from Magic to religion, to science and there is that Hegelian perception of moving from worse to better. And so there is also the use of a term that now in Anthropology we don’t use anymore which is primitive, primitive with a negative connotation, of course. And so what Frazer sees and other Anthropologists of the time saw was that Magic was associated with a proto-scientific time and a non-scientific time and it was at times associated with the irrational. So when he says a regression in consciousness it reminds me of that movement that Frazer sees in history from Magic to religion, to science where you are moving backwards towards, you know, if you see the history unfolding in that way, where Magick comes first then religion, then science he is talking about a rejection of religion, the monotheist religion and then getting to Magic, so the Occult. So it feels like you know moving backwards according to the representation of history that Frazer provides. So that’s the first perception that I got and then, of course, as I say personally reading these theses against the Occult. One other thing that I see is a complete oversimplification of what the things that he talks about are….

(Justin loses power to his house)

Oh, I’m alone now for some reason. What happened to Justin?

Anyway. So another thing that I was that I noticed is that there is, I think, an oversimplification of words, the things that he talks about are. So, for instance, when he says, “I believe in astrology because I do not believe in God,” I don’t really don’t see the association between these two statements and even if this is something that a practitioner has said that should be put in context. So that we can actually understand how this sentence relates to the wider belief system of the person that has made that statement. Whereas in this case, he’s just extrapolating a sentence where the two parts don’t have a direct logical correlation, I would say. And he’s just advancing a thesis that people that believe in astrology, believe in astrology because they don’t believe in God. Whereas maybe the belief system, the framework that that specific person had would have been much wider. And even in the case where that one practitioner was holding that view that they believed in astrology because they didn’t believe in God. They had to fill that gap because that’s what he’s implying here. He’s just one practitioner and that’s not what Anthropologists do. When you’re trying to understand a religious phenomenon and why people believe in Occult practices you cannot just take one case and in fact, one sentence. Because it’s not even put in context. You cannot just take one sentence and extrapolate an alleged understanding of why all occult practitioners believe a certain thing for a certain reason.

So also the idea that monotheism is decomposing into a second mythology, something that I completely disagree with.

And where is Justin!? What’s happening?

Sorry, let me check if I have Magick messages from here.

Oh, Justin has lost power.

Sorry, I’m asking Justin what to do.

So see that’s what happens when you are live – that anything can happen. So now I’m worried that I got too angry at Adorno. But I’m kidding. Justin will try and come back to the live stream in a few minutes. Try to see whether they get power back in a few minutes. It’s at least good that I can see you guys in the comments because at least I know what’s going on in the chat. Because sometimes you don’t really see the comments and Andrew, hi, Andrew. He’s saying,

“Adorno’s Geist is angry.”

Yes.

Can I show you my screen? Let me see if I can show you. I’ve never done this on… Okay, can you guys see the screen? At least I have company or maybe I have to add it to the screen. No, I don’t think it’s working, nothing is working today for some reason but let me know if you guys… No, I can see from the chat that you guys are not seeing it. Never mind.

So let’s get back to the first thesis. So going back to it, the tendency to Occultism is a symptom of the regression in consciousness and Justin was explaining that Hegelian view and I was contributing by saying that I think there are also links to an understanding of Magic that was popular in the 19th century and early 20th century, this idea that Magic belongs to a primitive time, a time that we have moved forward from. So you have the idea of progress. I think that we still have somewhat the perception that our history tends to move from worse to better but maybe in more recent years this Hegelian perspective of history has been has been challenged a bit more and I think that’s a good thing. And not because I would argue that history doesn’t necessarily move from worse to better, I would argue that things just change. So I see it more as an adaptation towards changing times rather than things becoming better. So they may seem better because now we are evaluating the past from the lens of today and from what we would find useful and necessary and worthy nowadays. So that’s why I think we may have the biased perception that the past was worse and the present is better and as a consequence that the progress towards the future is always something that goes towards something that is better. And since through the alleged secularisation, because the concept of secularisation has been challenged by Sociologists of Religion and especially Peter Berger, who’s a sociologist that I always recommend, who challenged the idea that we became a secular society, in fact, he argues that we became a pluralist society as opposed to a secular one because the idea of God and divine and of religion has not disappeared, it has just become more pluralised more, individually tailored and you have multiple religious systems multiple beliefs that interrelate.

“So the tendency to Occultism is a symptom of the regression in Consciousness, this has lost the power to think the unconditional and to endure the conditional.” I think this is very difficult to unpack, what he means by the unconditional and to endure the conditional. So I would need Justin here. Maybe we can get back to that later. “The unconditional becomes fact, the conditional and immediate essence. Monotheism is decomposing into a second mythology.” This is another aspect that I have a problem with. Monotheism is decomposing into a second mythology. One of the problems that I see here is that monotheism is seen as a religion. So it feels like he wants to say religion is decomposing into a minor mythology. But he’s saying it with the wording ‘monotheism is decomposing into a second mythology.’ So my perception is that he is equating monotheism with religion and of course, I disagree because there are many forms of religiosities that are not monotheist and then I have already commented on “I believe in astrology because I do not believe in God.” Basing a thesis upon one sentence that is not contextualised, I think that it is a massive oversimplification you will hear me say that a lot because I think that generally…

(Justin comes back online on his phone)

Oh, Justin is back. Justin, you’re on your phone.

JS: Yes, I’m back on my phone. Power’s still out but thank you for holding the line, Angela. So this is completely ridiculous having to stream on my phone but there may not be a lot of other options.

AP: So that’s fine. Have you listened to what I said or…?

JS: I did and do take the idea that lurking in the background is kind of a Frazeristic idea of the progress of religion in that way. But I don’t think he’s talking about it anthropologically. I’m going to change my position slightly so I can get a little bit more light. I don’t think he’s thinking about it anthropologically as much as he’s thinking about it in terms of this much more Hegelian sense of that it’s consciousness that same regression not that there’s like a movement from primitive religion to something else and this is why I think it’s the theses on Occultism not the theses against occultists because I don’t think he particularly cares about what individual people do. I think that his concern is about a movement in consciousness at the level of society, generally, that’s I think what his overall concern is.

AP* Can you comment on the sentence, “this has lost the power to think the unconditional and to endure the conditional?”

JS: Yeah, I think again this is more Hegelian stuff. The unconditional is the absolute, right, it’s that which is known is conditioned by nothing else and of course, that’s only God. And the idea of thinking in the conditional is that you have to climb the absolute you have to climb through the dialectic to get to the absolute through logic, there’s no other way to think the absolute other than the way that Hegel has lined out through the objective and subjective logic. And I think that if you can think the absolute without that process you could just experience the absolute. So the worry here is the idea that you no longer have to think the absolute, you can just experience it in some mystical way that both Hegel and Adorno find to be deeply sceptical. I think this is also our scepticism around unverified personal gnosis, right? You tell me you’ve experienced the absolute and I told you this but there’s no way for me to verify that because I can’t trace your steps and that’s exactly Hegel’s worry about people who claim to know the absolute or the unconditional becomes fact. The unconditional is never a fact in that way, it’s always the result of a larger process and I think that the conditional is an immediate essence. The conditional never has an essence because it’s always conditional upon something else and therefore one can’t take ideas, ipso facto and make them into essences and this is Hegel’s critical Platonism and ditto. The general critique that Adorno has of Platonic essences is things like minds and souls and spirits and anything like that. That’s his general anxiety there, there’s a mistake in thinking. You could disagree with them about that but that’s his concern.

AP: Yeah, I get that. I think that Adorno was also a fan of Kant. Do you see any Kantian elements here?

JS: For sure. Again I think that’s the whole thing is that I mean Hegel thought you could get to the unconditional through the dialectic but that’s it, that’s like it. And I think that that’s also a very Kantian point that you can’t think the numinal and that’s the claim that Mystics make, at some level as they can. I mean that’s the whole gain of gnosis, that’s the game of trying to get to the absolute, to get to the Gods, to get to God, is that the idea that you can think the absolute without going through the process of the logical dialectic. I think Adorno and Hegel and Kant are very sceptical of that.

AP: Although here Adorno says, “that instead of defining both in their unity and difference by conceptual labour it mixes them indiscriminately.” So he’s arguing that people in the Occult are mixing the conditional and the unconditional.

JS: That’s the mistake and that’s the term conceptual labour that’s just a dialectic, that’s the work of getting up through, climbing through the objective and subjective logic in that respect. Yeah and I think that’s his worry, right? Is that you take a word like spirit that for him refers to a very specific thing and he says this, right? Spirit is disassociated into spirits and therefore forfeits of power to recognise that they do not exist. The spirit is absolute you know Geist is absolute but then if you confuse the world of the absolute and make it into all kinds of spirits or diamons or demons or whatever or dead people or the spirits of the dead or whatever you’ve taken what is the transcendental and the transcendent and made it into the conditional and that’s the mistake.

AP: Well I think that in this case, he’s also trying to understand how the word view and the belief system within the Occult works with terms and a framework that is not particularly adopted by Occultists. So who says that there is a dualism there between the conditional and the unconditional and that you’re turning one into the other or mixing them together? You are already presupposing the very existence of this dualism that, perhaps, for somebody that endorses that belief in those practices, that dualism might not be there, to begin with.

JS: For sure. Yeah, I mean he’s very much a Hegelian chauvinist. I mean he also has stated that yeah, you can think whatever you like but this is critical philosophy, like their arguments as to why we can’t think the unconditional. You can say that you can think the unconditional but that’s grist for the mill of him saying you’re just saying things. And he goes on here to talk about the argument from phenomena and I think that the argument, the counter-argument would be no, I experienced this, I had an experience of this, I experienced this through the phenomenon. And what I think Adorno would say is, yeah people experience things all the time but phenomena are always conditioned, subjective experience, objective spirit is always conditioned by subjective spirit and just because you experience something, it’s maybe even more of a reason to disbelieve you as opposed to a reason to believe you. When you have to appeal to phenomenon alone that is more proof of the fact that, what does he call it? “The veiled tendency of society towards disaster lulls its victims in a false revelation with hallucinated phenomenon.”

AP: And not a phenomenologist feel.

JS: No, at least not a phenomenology, it’s The logical phenomenology of Hegel and not the subjective phenomenology of someone like Husserl or Heidegger for that matter. And of course, he’s going to go against that because he thought that all of that Heideggerian stuff was just fascist metaphysics. But I think that this last line or this last couple of lines, “in vain hope do they” and blah blah blah, “that this phrase panic breaks out once again after a millennium of enlightenment.” I find it interesting that he says a millennium of enlightenment. Again for him, enlightenment has been a long, long process. He’s not locating enlightenment in the 18th century, the way that we typically do that.

AP: so he is also including the time when Christianity was the hegemonic religion as part of the enlightenment.

JS: Yeah, I mean I guess from 947, I mean there were still Pagan holdouts then but I think that yeah, of course, he believed that there’s been sort of a slow tendency toward enlightenment but notice what happens in modernity. That the whole process goes off the rails at some level that the “humanity whose control over Nature has control of men far exceeds and horror anything men have had to fear from Nature.” For people who want to read Adorno as a hypermodernist, I think that you have to give up on that because he’s not a hypermodernist. He’s very critical of modernity and one of the ways that he’s very critical of modernity is the way in which reason itself has become its own mythology. And I think this is where I would push back against the idea that what he’s criticizing is the irrational, he’s not so worried about the irrational as much as he is a certain rationality actually and it’s this instrumental rationality that they talk about and in dialectical enlightenment. And I think that’s what he’s worried about, a kind of mystification which he calls Occultism that has now become united with positivism and that certainly happened in the early 20th century, in a big way.

AP: In what ways?

JS: Like the aim of religion, the method of science, to quote…

AP: Yeah but I wouldn’t call it positivist. For Positivists the only thing that is true is something that you can verify, whereas for Occultists, you know, you quoted Crowley, is not exactly the same as science, it’s not the same as Positivism because it’s not the case that only the things that can be measurable are considered to be positive or true. It’s more the sense that there is a perception that you can use the method of science with a different framework so that you can explore the Occult world, we can call it like that, even though it is an inaccurate definition, in a way that we can understand and explore. So it is more of a mixture of things because I think one popular understanding of the Occult that we find in Crowley, but also in other stories, is the combination of art, science and religion. So positivism is purely Natural Science and hard science whereas with these Esotericists you have more the combination of the method of Science and certain methods, not all of them, not the same framework clearly and also the combination with art and religion. So I really don’t see them as positivist to be fair.

JS: Positivism in the broad sense and again, there’s positivism all the way from Carnap and the Logical Positivists all the way… I think the idea is that what is worthy of belief is capable of being proved. Positivism in that broad sense of the word I think is how he is how he’s using it.

AP: The thing is that for them the way you prove it is not the way you prove it in Natural Science, it’s more about proving it with your experience.

JS: And I think he’s opposed to both of those. What I’m saying is that he’s saying that both an appeal to subjective phenomenology is going to fail but also trying to prove it in a purely positivistic way are also going to fail and that the Occult tries both. That is a symptom of its failure is that it has to appeal to what he thinks are basically two failed roads, that they’re taking up the same instrumental reason of the enlightenment that has actually already failed. And again he’s writing this in ‘47, he’s seen what he thinks instrumental reason leads to and that’s Auschwitz and so when I think what he’s concerned about here is that the Occult, broadly construed in this situation, is actually just recapitulating all the errors that it thinks it’s escaping.

AP: What would be these errors?

JS: Phenomenology, subjective phenomenology, like taking the unconditional as fact but also the idea…

AP: But that is not true because I don’t think they take unconditional as fact, they take unconditional – well they don’t use they wouldn’t frame it as unconditional, to begin with, and it’s more valuing the experience and exploring things beyond the conventional exploration of the world.

JS: And that’s the thing, that’s the dual line right, is that it’s both an error in phenomenology and it’s an error in the importation of instrumental reason. The more positivist side of things, as the psychical research people and things that existed at this time. He thinks it’s Scylla and Charybdis.

AP: Pardon?

JS: I think he thinks that it’s Scylla and Charybdis – that appealing to either is a disaster or will lead to an intellectual failure and that explains the regression. And I think what the larger question is here, is that he’s seizing of this line that, “the veiled tendency of society toward disaster lures its victim into a false revelation.” The play on there is a false revelation and false consciousness from Engels but I think that he sees what’s living inside of a giant social catastrophe and that one of those attempts to get out of it or to solve it is a regression back into religion and specifically in this form a religion in the form of Occultism.

AP: I just struggle to see the correlation between the two to be fair.

JS: Yeah, I think he’s just picking on a minoritarian way of trying to solve the thing and I think that this is, you know, we get this in some forms of Occultism in the mid-20th century where we have the idea of new aeons was coming out of someone like Crowley who had just died when this was published but also the idea of sort of traditionalism like let’s go back in time, to a time where things were where religion was pure before Christianity or Abrahamic beliefs corrupted it. And I think that what Adorno is going to say is that no, there’s no going back to a primaeval past before critical philosophy where you could just experience the unconditioned and anyone who attempts to do that is going to is doomed to fail at some level and nor is there a positivistic way out of this either where we can just simply go to a new aeon where science and religion get combined.

AP* I just don’t find it to be a compelling argument for me.

JS: I think it’s very powerful I think it’s like an interesting idea that he’s rejecting both the sort of Marxist, in the future there’ll be a utopia if we just like technologic our way out of this but also he’s rejecting traditionalism and saying there’s no past in which things were better. Like we have to be white-knuckled about now like we are on the Titanic, it is not sailing to a bright future and if you stay on it it will sink and he’s particularly pointing out one variant of it which he calls Occultism.

So I think it’s an interesting thing and I think this is the last maybe the last point I’ll make about this, is that its sort of an interesting admission on our part about how am I putting this. We allow the regression he’s talking about, regression, right? And again I’m using his terminology, I’m not sure if I believe in it but we allow the regression and it’s interesting that we allow it. Because if it were the case that we really did believe in a society that people could control reality through their will or through Magick or divination or can know the future, I think we would be even more vicious in persecuting it than they would have been in the 15th century. Because one we have the ability to do it through surveillance and we have the technology to do it through mass extermination.

AP: yeah and the fact that perhaps Magick works in different ways… so, sorry I should let you finish first.

JS: I think his point there is that we like we allow the regression because we all know it’s not real because if it were real in any instrumental respect then we would jump on it, there’d be the Army, the Navy, the Air Force, the Marines and the Sorcerers or something and the fact that it doesn’t do what it claims to be able to do is that we entertain it because it’s basically ineffectual in that way and I think that’s also what he’s worried about as well that it’s like polishing the brass and the Titanic,. That we tolerate it because we all need to cope with the terror of modernity and this is just one way of coping with the terror of modernity is by pretending we can control it.

AP: This reminds me of a theory by Ernesto de Martino probably the most famous Italian Anthropologist of the 20th century, who, when he was trying to understand Magic, talked about the idea that it solves the crisis of presence. Meaning that when the agent, in reality, feels like they are just an echo of the world and they are not the actual agent when there is a dissolution between the subject and the object there is this crisis of presence. And so Magick gives the agency back to the agent. So that’s de Martino’s explanation of Magick through the crisis of presence. But going back to your point if Magick worked, people wouldn’t allow it to happen. You know it’s a bit more complicated than that because the way Magick works, according to practitioners, is not necessarily something that you can measure in the same way as you can measure something that is part of an experiment in Natural Science. So practitioners would claim that the way Magick works is very different and even though practitioners tend to claim that there is a degree of success, a high degree of success, well it depends because… that’s another thing that when we discuss Magick. Usually, there is this sense of polarisation that either it works all the time and then it means that it is quote, unquote real – that’s another philosophical, ontological category that should be unpacked before I use it or it doesn’t work and it is unreal.

Whereas for many, many practitioners, in that sense, perceive Magick and use Magick and work with esoteric practices in a way that is akin to science in certain ways, but also to art in other ways and to religion as well. So there is the sense of repeating things, for instance, Magick workings over time to see what kind of correspondences work best for achieving a certain result. But the issue is that with natural science things work by causation, the combination of correlation and causation. Usually, they say correlation is not causation and to understand how things work you need to find the cause and once you have found the cause you can reproduce it according to the cause. Whereas in Magic and esoteric practices, you have acausal connections and they are still believed to work by practitioners and practitioners report to have results from them but it’s not something that you can test through the current scientific means, I would personally argue, but I know there are also people that would argue otherwise. Well, I guess most people would argue that you cannot prove that Magick has any effect but there are a few scientists now, I know some that would want to prove the fact that there are there is an effectiveness to Magick. Whether that is possible is debatable because as I said I tend to think that Magick works in quite a different way. But sorry, maybe I went off on a tangent.

JS: No, I think that may be grist for his mill is that the fact that modern people practising Magick feel the need to subject themselves to any sort of Baconian framework means that they’re primarily operating in a modern epistemology. And so in that way he just says that modern epistemology has failed like it did not do the things that we thought it would do. In that way he would, I think, what he’s saying here is that insofar as that’s true that they’re operating within that sort of that larger Baconian framework then they’re not fundamentally different than the kinds of mistakes that modernity has already produced.

AP: And what are the mistakes that modernity has produced?

JS: I mean just the idea that Nature could be controlled, that the domination of Nature was possible or even advantageous. The domination over Nature includes the domination of other human beings.

AP: Yeah, but that’s also another instance that would be another misunderstanding of how the Occult Nature is perceived. Because there have been traditions throughout history that have seen Nature as something that would be controlled by the Esotericists or the Occultists or the Magick-practitioner. But there are other traditions that see the other in a completely different way, meaning that Magick is actually working within Nature. So it is through a state of interconnectedness that you affect the fabric of reality, not because you as a person are distinct from Nature and so you are imposing your will over Nature it’s more because you are so immersed and so connected with every aspect of Nature that, you know, something that is at a distance from you becomes your arm so it’s like I can move my arm because this is my body. If I extend the perception of my body to the entire universe then I can move things at a distance because that becomes like an extension of my arm or an extension of my leg. And you have perceptions like that even in the past where Tomaso Campanella, for instance, and the idea that the whole universe is a living animal. So I think that that’s why I was reading this thesis. In a way, I was struggling to understand even his thesis because I find that his definition or the definition that emerges of Occultism is so difficult to grasp because to me it’s an oversimplification. And I’m trying to understand which aspect is he picking up on because it’s clearly not what Occultism is, it’s just an element of it that he is picking up and analysing. So I think that the one that he’s analysing is what you just said, that’s why I asked the question, the one that supposedly imposes the will of the person over Nature. But you have many traditions in Esotericism that have a very different view, they don’t see the human being as all-powerful they see the human being as part of Nature and it is through the connection that Magick happens.

JS: Right, and I think of people like of Campanella and della Porta who both see Nature in that way but also see it as something to be instrumentalised.

AP: Yeah, like, you know, but that doesn’t imply that one is instrumentalising the other. It depends on whether you are framing that as a dualism or as a monism because I can say, I can instrumentalise my legs to squat at the gym but I’m not seeing the legs as something different from me, it is still part of me. So it also even the way the instrumentalisation is conceptualised is very much dependent on the belief system and the worldview that the person holds. So this is another problem that I see in Adorno’s understanding of the Occult.

JS: I guess it’s not so much who’s instrumentalising whom but the reason itself is instrumental in its Nature, that’s his concern.

AP: The reason itself for the Occult is…?

JS: No, that the emergence of instrumental reason in modernity, that’s one of his big concerns, is that the idea that reason is an instrumental thing. I mean this applies to his theory of art and other things as well, that reason is never instrumental it’s never about what you can do with it, it’s about thought and that’s what it connects back up to the whole business of the conceptual labour and thinking the unconditional and all that.

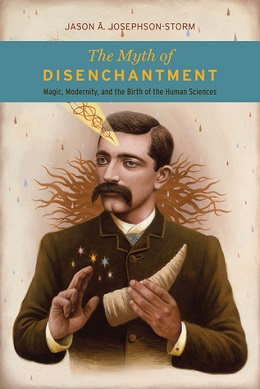

I mean I think what he’s doing and I think this is a point that he makes in Dialectic of Enlightenment and what’s his name (Jason Josephson Storm) makes in The Myth of Disenchantment is that…

AP: Weber, Max Weber.

JS: Right… that what we call Western Esotericism or the Occult is actually incredibly modern and that, in fact, in all the places where we think we see disenchantment, it’s there. And the modern discourse is to say well disenchantment never happened and what Adorno’s saying is no, disenchantment did happen right or that disenchantment didn’t happen and that’s precisely the problem. That we nevertheless never left disenchantment, it’s still here with us – it just became modern enchantment, became modern and we called it disenchantment but it never was that. And it had all the same deficiencies as modernity did that we think of someone like Bacon or Kant as being the tip of the spear of Enlightenment and reason but that same form of reasoning, that led all the way to Fascism, is absolutely just there in other things as well, especially as well as in this. So then in some ways, I think that the idea of the myth of disenchantment for Adorno is, Adorno would say, hey you’re knocking on the open door. I know it didn’t happen and we have the 20th century to prove it didn’t happen. And Occultism is not what he called Occultism, it is not an instance where something came roaring back from the past rather this is actually just the result of a certain kind of reason regressing, in the same way, that reason regressed when people used science instrumentally to kill people for no reason or racism or whatever. Else he’s just saying that.

AP: How does he describe progression then I’m a bit confused.

JS: Regression in the sense that, in the very straightforward Hegelian sense that reason is there to make us free, at least in the realm of subjective spirit, but it didn’t and he’ll talk about this later, that the occultist sees spirits all around them and it makes them terrified that they themselves have created and they’re not real, that they created a false world that they scare themselves with. Now rational people will look at that and think why would you do that to yourself? But Adorno’s point is perfectly reasonable, people did that, they were called Germans they created a horrifying system of violence and then oppressed themselves with it. And he’s saying yeah, you so-called rational people when you laugh at Occultists summoning demons, you think they’re ridiculous, but you summoned fascism. And these are the same things – they’re both creating worlds that are not real and they are power-creating worlds that are fundamentally from human beings, through instrumental reason and afflicting themselves with it. He thinks they’re both in that way regressions.

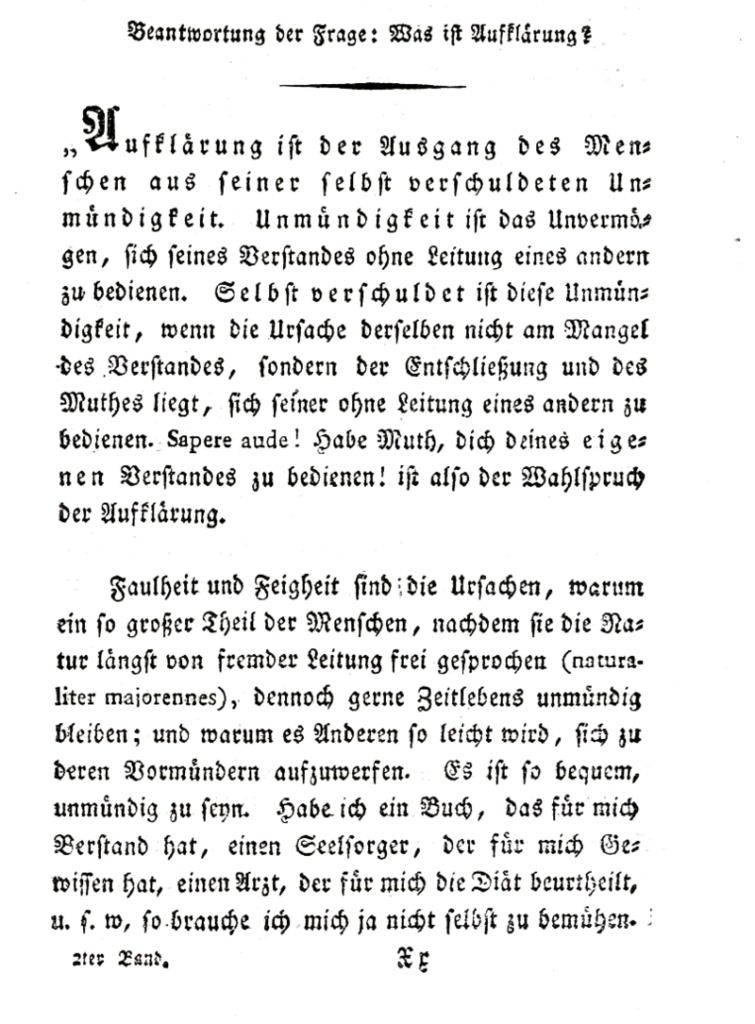

And they are both regressions of consciousness if Kant was all about “Was ist Aufklärung?” right that you know Superior all day if that’s Enlightenment and Enlightenment led to fascism and Occultism is supposed to be about getting power or experiencing the absolute or mystical union with the one. He thinks all this has failed and failed along the same lines and that I think is a terrifying critique.

AP: I think that I would disagree with that as well. I was trying to unpack in my mind the idea of Occultism or Occultists that creates their own worlds and I was about to say that that’s not necessarily true. But I think it could either be true for everybody because we all have our own representation of the world because and this is perhaps a bit Kantian but we do not receive just the word as it is, we receive the world and then through our senses and then interpret it. So it’s not just through the senses and through time and space it is also through our own worldview that we interpret what is in front of us. So in that sense, we could easily argue that everybody creates their own worlds, not just Occultists. I mean worlds that are not true because that was what you were talking about that in Occultism they create worlds or a world that is not true and then operate within that or with that. But that’s probably something that we all do, Occultist or not because we all have a certain representation of the world, a certain worldview that becomes the lens through which we see reality and we sort of absorb reality because it’s not a direct absorption, it’s always filtered. So in that sense, I would say that Adorno also had his own false world that he created, through which he interpreted the things that he was talking about and clearly misunderstanding Occultism.

JS: And I tend to agree with you at least in one respect of that but I guess I would say that it’s not Kantian to say that all the worlds which individuals experience are all equally true. I mean that’s certainly not what Kant believes.

AP: No, by Kantian I meant the idea of receiving the world as a filtered one, not having a direct access to what is out there.

JS: Right, and I think Adorno thinks that too. And again I picked on fascism earlier but I think that the general critique here is of totalitarianism, it would also be of Stalinism just as much as it would be fascism. All the fascism is especially irrational he thinks but… Yeah and I guess that’s the big difference I think between Adorno and maybe myself and maybe you, Angela, is that like Adorno is a pretty hardcore realist and I think that you would be much more comfortable with… relativism is maybe not the exact right word but at least a plurality of phenomenological worlds

AP: Yeah, sometimes I define myself as an active Nihilist.

JS: That’s even more radical. So I didn’t want to put that in your mouth. Yeah and he’s certainly not and he definitely believes in the absolute, although the absolute is obviously mediated.

AP: Well, I would argue that it’s much more dangerous to believe in the absolute and be a realist because that when you have this kind of perception, you have a right and wrong way of looking at things. And if you don’t have the right way, using a realist perspective, the fascist, from their point of view, they had the true understanding of the world. Whereas I think that a form of relativism that takes into account the effect that you have on the community is much better suited for perhaps utilitarian ethics where you try to be the most advantageous that you can for the most people and the less harmful for the most people because we’re all very different. And I do think that people see the world in completely different ways depending on their belief system. That’s why I think that religion and Religious Studies are so important and should be studied much more because they have a definite impact, also on politics and society at large. So I think that a realist perspective and endorsing the idea of the absolute and absolute reality that is out there. That and you know, if you don’t see that you are not seeing what is actually real – is much more dangerous. And I would say that that’s probably what the fascists and the Nazis thought, that you cannot have a different perspective on how things are because the way things are was the way they thought about things. So I think that’s much more dangerous whereas a relativist view of reality and of the world I think that is more beneficial, acknowledges the plurality and the differences. But, of course, even the relativist view of reality needs to take into account society at large. So it’s not insular and it’s not solipsistic.

JS: Right, and I think Adorno isn’t an absolutist in the sense of he knows, he claims to know the absolute. I think he says that there is an absolute and we can be less wrong about it.

AP: Yeah, because he had, what was it called, the negative?

JS: Yeah, the negative dialectic.

AP: Yeah, negative dialectics.

JS: Yeah he doesn’t think that he knows what’s right, he just knows how to be less wrong.

AP: Yeah, but it is still an approximation to something that you would define as truth.

JS: Sure because I think that he thinks that relativism basically means that everything becomes a utilitarian calculus at that point. And again, that would be worrisome for him because of his worries about instrumental reason, that people become reducible to quanta of pleasure or something, pleasure and pain. And that kind of reasoning terrifies him. Because again, he lived through that kind of reasoning when we dropped the atomic bombs or when the Germans decided that some people were worth living and some people weren’t or when the Stalinists decided this is how many calories that these people get and that people got reduced to quanta and that utilitarian quantizing I think he thinks is again Kantianism and instrumental reason writ large. But neither here nor there, I think that’s why he would be worried about relativism backed up by utilitarian calculation because it’s all about who’s doing the calculations.

AP: Yeah, I think the utilitarian if, you know, it’s more useful when it is a soft utilitarianism and also when it just sees all people as equally valuable. So I think, when it becomes something that is based upon the idea that certain people are more valuable than others, then I’m not sure I would see it as utilitarian in my perspective at least.

JS: Right well it’s not so much that who are some people thought better than others it’s just that no one was thought to be human, they were thought to simply be quanta of pleasure and pain and in that humanity’s loss. I think they could even argue that in “Dialectic of Enlightenment” what is human is lost in the calculation. But also then again I’m not arguing in defence of Kant either, he also thought that Kantianism failed for different reasons, that it also made us into people who couldn’t do right, basically. Again this is what is unnerving about the critical theory is that we want them desperately to tell us what the right answer is and then they won’t because they think they can’t, that they think that that praxis is done through doing, not through theoretical discourse and so people are like well, they just criticize and that’s all they do and I’m like yeah, that’s what they do.

But may we turn to the second thesis?

AP: Okay.

JS: To get bogged down in so many other things. Do you want to read through part of this one and stuff when you want to we can talk about it.

AP: Okay

JS: And then also be mindful of your time. I’m sorry that the power went out – it’s still out actually.

AP: Yeah that’s fine. I think we can stay for another, I don’t know, 15 minutes or so.

JS: Okay.

AP: So we can start the second thesis.

“The second mythology is more untrue than the first” and this is referring to the fact that he said that a rejection of religion leads to the second mythology that he associates to the Occult, “the second mythology is more untrue than the first. The first was the precipitate of the state of consciousness of successive epochs each of which showed its consciousness to be some degree free of blind subservience to Nature than had to previous. The former, deranged and bemused, throws away the hard-won knowledge of itself, in the midst of a society which, by the old-encompassing exchange-relationship, eliminates precisely the elemental power of the Occultists claim to command.”

JS: Yeah we can unpack that one a little bit.

AP: I think it’s honestly difficult to understand what he even means here. It’s very cryptic, the second mythology is more and true than the first – okay, if you say so.

JS: What I’m saying, by the way, is that monotheism is also an untrue mythology.

AP: Yeah, but he’s saying the second mythology is more untrue than the first.

JS: Right, so Occultism is more untrue than monotheism. So he thinks that both of them are mythologies.

AP: Yeah, so the first was the precipitate of the state of consciousness so what does it mean by the precipitate of the state of consciousness of successive epochs? This is still Hegelian. So does it mean that even monotheism is losing the sense of freedom? Each of which shows this consciousness to be some degree more free of blind subservience to Nature than had the previous.

JS: Right, that’s Hegel, that’s how you go theory of religion, that as we became free from Nature. We’ve developed a deity apart from Nature that originally Nature and God were the same things and that as we became free of Nature and civilization we detached the Gods from Nature and they became like us, like our attachment from Nature is mirrored in the heavens that like the Gods go from being one with Nature to being beings like us living in somewhere that’s not natural, like the heavens or whatever. So as we freed ourselves from Nature the Gods became separated from Nature, they became alienated from Nature too and also eventually it became now much more like us. And of course, that took time he thinks, that the state of consciousness is a successive epochs That separation from Nature yielded God separated from Nature and the domination over Nature ultimately resolves to the fact that we don’t need the Gods at all. The Gods would vanish, or the Gods would vanish and that the absolute would remain. But for Adorno, being a materialist would say no, what should happen is that even monotheism would be revealed to be a mythology.

AP: And why is the second mythology, AKA Occultism, more than truth?

JS: I think it’s the second statement. The former – wild, deranged and bemused or had hard-won knowledge. It had gone through a process by which over successive epochs, they had won an evolving nature of how they conceived the Gods. And Occultism, according to him, is less true because people went through hard work getting rid of the Gods, like people spent 5,000 years getting rid of the Gods and now someone comes along and puts them back. It was hard work to get rid of them. We had to conquer Nature we had to dominate Nature and again Adorno thinks that’s a bad thing, right? But the upshot of it was we separated ourselves off from these mythologies where we thought of ourselves as dominated by sky-dad or whatever. And now that we know that sky-dad’s not real, well now we can free ourselves and not be dominated by sky-dad anymore. His worry is the Occultists have gotten sky-dad back.

AP: Well that’s because he doesn’t really understand the Occult.

JS: For sure and I think that he would say that it’s anyone who’s benefiting from the benefits of secular society, resurrecting mythologies as if they were true, who gets to basically enjoy all the benefits of all the generations prior to them who had to do the hard work of freeing themselves from the fear of the Gods such that people in the lap of luxury can interact with these alleged beings in a way that’s safe. Because people were terrified of the Gods in antiquity. But is anyone really afraid of them anymore? I mean they’re less powerful than the kings and queens are now. I think that’s his worry.

AP: Yeah, I think that sometimes and maybe I said this before, but I struggle to understand his position just because I try to associate his position with Occultism and it’s not equal with Occultism, the way I know it. It’s more associated with his fantasy of Occultism because I would disagree also with this perception of the Gods by Occultists. It’s very, very different from ancient times and very, very different from sky-daddy, which sounds a bit kinky. But anyway.

JS: With lightning to punish you.

AP: Yeah, but because he’s writing this in the 20th century, it’s not how 20th-century Occultism would see the Gods, I’m trying to sort of remember the different traditions that were out there at the time but I really don’t think so. And yes, of course, secularisation has affected the way Occultism has been seen and conceptualised and practised. So in a way, and this is something that I also talked about in my video on Satanism and how Satanism became a romantic hero because after the enlightenment all the metaphysical entities and spirits were seen as less real, not as real as us and so they become more inoffensive and so when you have that shift in perception then they can acquire different characteristics. So, for instance, you have, especially after Jung, the perception that Gods can be archetypes that you work with, that they can be part of yourself and you work with them. So it becomes something that is completely different from how the Gods were perceived in ancient times and even in that case it really varies from culture to culture. But definitely in the 20th century, the perception of the Gods was not like that and not comparable, I would argue, with a monotheistic perception of a God.

JS: Well, I think you’re right. Certainly, they underwent an alteration in modernity but I think that his worry is that in the midst of a society which way all income-passing exchange relationship eliminates precisely the elemental power the Occultists came to command. I think his worry there is that, and of course, this is elitism speaking, and he says it’s even right that there was a historically appropriate time to experience those kinds of things but that time has passed.

AP: So what is the problem? So I think we have to repeat it multiple times so that we can better understand that nobody….

JS: He’s super difficult. I think that what he’s saying is in pre-modernity it was appropriate for people to think they were talking to spirits and Gods and things like that, but now there is no excuse for that anymore.

AP: Except he’s not taking into account different conceptualisations of entities that practitioners endorse.

JS: Or at least that. I mean, I’m not sure what you would say about Jung because he did they did have a big interest in psychoanalysis but I think that, is not real, in the sense that they have no ontological standing as metaphysical beings.

AP: Yeah this is something that in Pagan Studies we call soft polytheism and hard polytheism, so you have some practitioners that lean, and it is a spectrum it’s not like you’re either or, but there are some practitioners, some Occultists, Esotericists or Pagans that believe that the entities they work with are ontologically real and distinct from us and soft polytheists tend to see the entities they work within their practice as archetypes, psychological archetypes or as forces of Nature. So his critique of Occultism is again disregarding Occultism, it is just his own view and in my reading of this, not only does it have a misunderstanding and oversimplification of Occultism and lumps together things that might not necessarily be related but he also tends to understand Occultism from a monotheistic lens. Because within Occultism and looking at the texts written by Occultists at that time that is not how they would talk about their Gods or if he had bothered to read those maybe he would have had a better understanding of what he was talking about to begin.

JS: Well I think here he’s going to mention in a minute, I think he has here and he cites people like spiritualists who believe they can talk to dead people. That’s who he has and does not sort of like…

(Justin’s phone mutes for a few seconds)

… but I think he has in his sights here people who think that they can do things like tell the future or talk to dead people and not like trickery but like people who legitimately thought that they could communicate with the spirits of the dead, that they were human beings that had died, their spirits lived in some other place and that people could talk to them.

AP: Yeah, but you see this is something that I was mentioning earlier, before we went live, the spiritualists were rejected by most of the Occultists of the time. So it is true that there were, and as I said, I even mentioned the idea of hard polytheism and there were at the time people that would believe that there were spirits or spirits of the dead or spirits that actually existed but that was not particularly prevalent, I would argue. And also spiritualism specifically was rejected by all the other Occult traditions of the time, it was rejected by Theosophy, was rejected by the Golden Dawn it was rejected by Aleister Crowley. So that’s why I also think that he lumps together things that would have not been considered as being part of the same milieu from the point of view of those who were actually believing and practising those things. So he’s coming from a point of total ignorance of what Occultism was at the time.

JS: Or he just doesn’t he doesn’t care about those. I think he would say that the narcissism of minor differences between people who believe these things doesn’t really matter to him. That at some level, in the same way like critiques music, he doesn’t care that the people who play the music, the different genres of music that he thinks are inferior to, I don’t know, 12-tone Schoenberg – atonal crazy music. He doesn’t care that they’re that they would disagree with each other. He says no, you’re all part of the same culture system and so far as you’re part of that then it’s open for a critique.

AP: Yeah, well I mean it’s fine I mean as a scholar you can create a category and then analyse it but the problem is that it’s not acknowledging, it’s just not accurately understanding what Occultism is, to begin with. Or certainly not accurate to our conceptions in the 21st century but I wonder in 1947 if you were looking from the outside and you want to do a philosophical analysis of what is broadly considered as Occultism, Spiritualism, I think, would have been included in there.

AP: Okay, well he included it so clearly that’s at least one person and probably a few that would have included it, it’s just that it is an inaccurate representation of what Occultism was at the time I also don’t really know what kind of source material was available at the time. Because now obviously, we have much more knowledge of what was going on in the 19th, early 20th century because we also have more texts available. I would imagine that Adorno wouldn’t have had access to as many texts as we have now.

JS: And I think he wouldn’t have read them if he had access to them, to be frank.

Do you want to finish this paragraph or do you want to call it quits for the day? I know we’ve been going for about an hour and a half.

AP: Yeah, maybe we can continue next time. We don’t okay where we are if I have a pencil or pen. Sorry folks that my power got knocked out, it’s still out. This is like the third time this has happened. Like once it happened when I was recording something with Dr Dzwiza and then it happened with Zevi in Cleveland and now this week. It’s the third time that the power is just randomly going out when I’m trying to do these live streams.

I think it’s a sign.

AP: That you shouldn’t do them.

JS: No, it’s a sign that I should do them but that there’s a conspiracy against me and therefore all the more reason to do them.

(Laughs)

AP: Makes sense.

JS* No, I wish that I were important enough that there could be a metaphysical or physical conspiracy against this YouTube channel. When and if that happens then I will have arrived. But that is definitely the case, it’s just windy outside

AP* Andrew is suggesting in the chat as we do the next episode on my channel.

JS* Yeah, that sounds fine to me either way. Angela, thank you for discussing this cranky mid-century German guy with me.

AP: Yes and I hope I didn’t come across as too angry.

JS: No, I think it’s a great point that again it’s one of those things where I wish we could go back in time and sit down with Adorno now and ask him, like what do you mean by Occultism bro? I’m not sure you would have actually given us that great of an answer. But yeah, we’ll pick back up with him sometime soon. So all right, let me see if I can climb out of this thing from my phone.

AP: Because obviously, from my end I cannot end the live stream

JS: Right I want to see if I can’t do it.

AP: Or we will have to stay here forever.

JS: Yeah, we’re trapped in the Occult world forever with, god forbid, Adorno of all people, of all the philosophers that don’t want to be trapped in a room with.

AP: Agreed.

JS: Not Adorno. All right, folks, I think I can end it here.

First streamed 16 Feb 2023